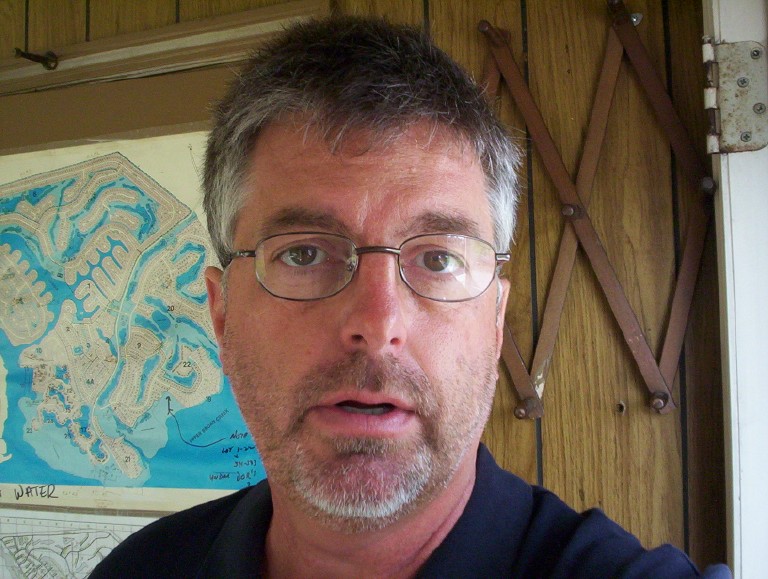

Brian Linse

dr george pollard

Introduction

Famous, on-line, for sensible liberal blogging, off-line Brian Linse, below, produces hit movies. His movies include, “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead” (2007); “Callback” (2005) and “Den of Lions” (2003). In 2012, Disney releases “Tiny Dancer,” on which Linse is Executive Producer.

Linse is no common blogger. His posts are astutely aware, his renown earned. There’s an implicit sense, in a Linse blog, that he ponders what others write and considers how he might take the debate forward.

Bloggers are typically narcissistic, impromptu and careless, but Linse is not. Driven by good sense, not ego, he reflects, posts and earns fame. If more followed his lead, the weighty claims of bloggers would come true.

For many, Hollywood producers flock with bloggers. Greedy pushers of hopes and dreams is a common image of movie producers. Brian Linse is the exception.

“In Hollywood,” says Teddi Kohl, “everyone rushes to save money or leap on an opening. Quality suffers, as a result, and art is nowhere. Everyone except Linse, that is.”

Linse produces movies as he blogs, with comity, calm and conviction. “Brian wants his movies to matter in 200 years,” says Neal Gumpel, the screenwriter. “Quality is his goal.”

“I read the original script for ‘Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead,’ says Kohl, a movie veteran, who prefers the alias. “The script was weak, but Linse saw potential that no one else did. He optioned [the script]; found a way to involve Sidney Lumet and Philip Seymour Hoffman and made a superb movie. ‘Devil’ made the AFI Top Ten for 2007.

“The key, I think, is Linse took his time. A dreadful movie is a certainty, if you rush.” Linse made “Devil” the way he blogs, with patience and care, which explains its success.

“When a Hollywood producer is on the set,” says Gumpel, “the truth is he or she is across the street, somewhere. They’re on a phone. They’re trying to line up the next ten deals.

“Not Brian Linse: he’s honestly on the set. He’s smoking a cigar, taking note of all the details. I don’t think Linse makes many mistakes twice; he’s that thorough. Few Hollywood producers take such an active role.”

“Hollywood is a factory town,” says Leroy Jones, an entertainment veteran, who prefers an alias. “In all factories, output is critical. If books don’t come off the printing presses, no one makes money. Hollywood, for all its claims to artistry, is an assembly line.

“The Hollywood prescription is simple. Make a movie. Find a way to make money from the movie. Repeat as often as possible.

“Once in a long while, someone comes along who can make art satisfy the needs of industry; Brian Linse, for example. He cares about quality and understands the movie business. The combination means long-term success.

“I can’t say I know, for sure,” says Jones, “but I suspect Linse is widely envied, in Hollywood, for knowing how to make art meet industry.”

In this exclusive interview, Linse talks about movies and movie-making. He’s candid about Ethan Hawke and “Devil.” He readily reveals Hollywood secrets.

don’t get the title of that film

Grub Street (GS) You’re from Chicago.

Brian Linse (BL) Yes, from Irish and German immigrants that settled in the Middle West.

GS Chicago doesn’t strike me as a major centre of Irish or German immigrants.

BL My father is second-generation Irish. There are many immigrants in Chicago. The city is the archetype melting pot.

GS What’s the origin of your surname, Linse?

BL It’s German. Seemingly, Germans prefer to name inventions based on what the item resembles. Modern eyeglass lenses appeared in Germany, in the middle nineteenth century. These lenses resembled lentil beans. The German word for lentil beans, linse, pronounced “lintsa.” My surname is simultaneously the German word for lentil beans and eyeglass lens.

GS That’s interesting and funny, in a good way.

BL I prefer to think of my name as the word for lens, not a bean. Some good irony, when my name is a lens, given the business I work. By the way, the way we pronounce the name, “Lindsay,” which takes it away from the German and more toward the Irish.

GS Irish heritage, that’s where you got the title of your last movie, “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead.”

BL Yes and I understood it. Many people, to this day, don’t get the title of that film. I’m Irish enough to understand the blessing qua title immediately. As soon as I finished reading the script, by Kelly Masterson, I understood the title, which is part of an Irish blessing.

GS Yes and in full, the blessing is, “May your drink be ever full. May the roof over your head by always strong and may you be in heaven half an hour before the devil knows you’re dead.”

BL The idea behind “Devil” is a specifically Irish sense of humour. We’re all sinners. We should all go to hell. There’s no doubt about that, but here’s hoping you can sneak into heaven before the Devil knows your dead.

Many people mistakenly interpret the blessing. They think, “When the Devil knows you’re dead, you’re kicked out of heaven and going to hell.” No.

The meaning of the toast is, “May you cheat the devil out of your soul.” If you make it into heaven before the Devil knows you’re dead, you’ve beaten him. You’re in heaven, even if maybe you don’t deserve it, but no one can get you out. That’s an Irish sentiment and what the central characters, in the movie, try to do: slip, without notice, in a clumsy way.

GS Did Sidney Lumet, the director, of “Devil,” get the idea?

BL I had to explain it to Lumet. He’s Jewish, not Irish. He loved the idea, though, and signed-on after we talked on the phone.

GS Can you briefly summarize the plot for “Devil”?

BL To get out of debt, two siblings decide to rob a jewellery store. Their parents own the store. The robbery goes horribly wrong. One brother hires his friend do the robbery. There’s a shootout during the robbery. The robber kills the mother. The robber dies, too. The characters descend from there.

Ethan Hawke, Albert Finney and Marisa Tomei

GS Most of the characters in “Devil” are going to hell.

BL Yes, they’re horrible men. Still, they’re like the rest of us. There’s nothing arch-criminal about them. After a series of poor decisions, they become desperate, hopeless and horrible.

This is the idea behind the movie: ordinary women and men, without especially big dreams. The heist, at the centre of the movie, is only worth $60,000 to each brother. They weren’t going to make much money from the robbery and, maybe, only get ahead on their debts.

The brothers hope to get through another day or two and figure out the more distant future as it arrives. This is an Irish sentiment, for sure: today, tomorrow and then we’ll see. Best way, of doing this, that they can devise is rob a jewellery store owned by their parents.

GS The original toast goes to human frailty and vulnerability, I think.

BL Yes, and so does the movie. I also believe “Devil” offers a condemnation. The movie takes a shot at modern American values, ideas and attitudes. Debt, driven by greed, leads to desperation in “Devil” and in the daily lives of many Americans.

Greed is so pervasive. We don’t recognize or question it any more. Robbing a jewellery store, owned by your parents, and murdering your mother in the robbery, is a reflection of 21st century American greed. No price is too extravagant for instant gratification.

GS How did you get Phillip Seymour Hoffman to star in "Devil"? (Hoffman, above, left, with Ethan Hawke)

BL That’s an interesting story. I had Hoffman before I had Sidney Lumet to direct. It took me five years to get “Devil” made into a movie. There were bits and pieces floating around, which eventually came together.

I sent the script to Hoffman before he did “Capote.” My first interest was for him to portray the “Hank Hanson” character. As it turned out, Ethan Hawke portrays “Hank” and Hoffman portrays “Andy Hanson,” the older brother, who plots the robbery.

When I hired Lumet, he rewrote the script. In the original Kelly Masterson script, “Hank” and “Andy” are friends and co-workers, not siblings. “Hank” was older than “Andy,” who’s also his boss, at work.

Masterson wrote “Hank” and “Andy” to underline the extent “Hank” is a loser. Relations among the characters were different in the Lumet rewrite. Injecting the family, as Lumet did, added a vital edge to “Devil.”

GS I don’t see as much interest if “Hank” and “Andy” are co-workers or even friends.

BL The Lumet rewrite floored me. He rewrote “Hank” and “Andy” as brothers. My response was, “Oh my gawd, why didn’t I think of that?”

Lumet gives “Devil” a different energy. He made the story much more intense and much more interesting. Now, “Devil” is about the messed up Hanson family, who use crime to solve problems.

GS Messed up for sure, as not only “Hank” and “Andy” use crime to solve problems.

BL In hindsight, I should have guessed how Lumet would rewrite the script. All his movies focus on two themes, crime or social justice and family dysfunction. His rewrite focused the script on a combination of his main themes.

GS Right, that’s true, but back to Hoffman.

BL I set up a meeting, in New York City, for Lumet and Hoffman. Lumet wants to work with Hoffman. He says, “Oh my gawd, I love Phil Hoffman, I would love to work with him, set-up a meeting.”

Hoffman is no dummy. They meet and he says, “I love this script. I love [your work to Lumet]. I want to work with you, but I don’t want to play Hank, I want to play Andy.”

Lumet says, “Phil, you can play “Gina [Hanson]” as far as I’m concerned.”

Lumet gives Hoffman the role, of “Andy Hanson.” My view was I hired Lumet to direct my movie. I can’t and won’t tell him how to cast the movie. The one job Lumet does better than do most directors involves casting a movie.

GS It’s hard to disagree with his casting decisions. He used a young Bruce Willis as a court spectator in "The Verdict."

BL I lined up behind Lumet. I had authority to overrule him on the four lead roles, which influence financing a movie. If the four lead roles are not bankable, no one will put up money for a movie. After the four leads, which we agreed on, anyway, Lumet cast “Devil” as he wished.

GS How did Ethan Hawke get the role of “Hank”?

BL When Lumet tells me Hoffman will portray “Andy,” I ask who portrays “Hank.” Lumet rewrote “Hank” as the younger, loser sibling, with “Andy” older and supposedly in control. Lumet thought Ethan Hawke was the ideal “Hank.”

I thought Hoffman and Hawke were too close in age. Audiences wouldn’t buy a ten-year age difference. I was wrong.

Next, I wondered if audiences would accept Hawke, as “Hank,” who’s a loser and more than a little stupid. Hawke usually portrays likeable characters, with which audiences empathize. On paper, “Hank” is a dark, unlikeable character.

I figure that if Hawke doesn’t pull off the “Hank” character, the movie flops. I said to Lumet, I don’t know about Ethan. I love him. I think he’s an exceptional actor, but I think he’s just too beautiful to be this character. If Hawke doesn’t create empathy, from the audience, we’re out of luck.

Lumet says, “I understand your concern, but trust me, [Hawke] will pull it off.”

After watching what Hawke did on his first day filming, I knew I was wrong about him. At that point, I knew he hit the role out of the ballpark. To this day, Hawke is my favourite actor in the movie.

GS I read you originally offered the “Charles Hanson” role, the father, to Paul Newman.

BL Yes, but Newman declined, graciously. In retrospect, I see our offer came about the time Newman became gravely ill. Albert Finney got the role and his portrayal was exceptional.

Albert Finney is one of my favorite actors. When I was a teenager, I did a trip to London and saw him in a restoration comedy at the National Theatre. Since then, Finney is on my A-list.

It was by no means a disappointment to get to work with Albert Finney, but, commercially, we had to offer it to Newman, first.

GS Is it true “Devil” won every award for which it competed.

BL Just about and for 2007, “Devil” made the American Film Institute (AFI) 10 Best Film List, which isn’t in any given order. “Devil” was on that list with “There Will Be Blood,” “No Country for Old Men” and “;Michael Clayton.” The AFI listing was the best, for me.

“Devil” was also up for two “Spirit Awards,” including Best Screenplay. The best actor nominees included Marisa Tomei (above), who portrayed “Gina Hanson.” We didn’t win either award, but it was exciting.

GS I thought the Spirit Awards were for independent or “indie” movies.

BL Well, “Devil” was an independent film.

GS It was an indie film.

BL “Devil” was an independent film, in every way.

GS It doesn’t watch as an indie film, more as a studio film.

BL Well, that’s Lumet. He was a studio filmmaker, most of his career. It shows.

Most of the cast are studio actors, too. Tomei won an Oscar� for “My Cousin Vinnie,” a studio film, but now she’s queen of indie films. After “Devil” and “The Wrestler,” she’s in high demand.

Hoffman and Hawke distract from the fact it’s an indie film. Their success makes us think of them as studio actors. In fact, Hawke and Hoffman are New York theatre actors. As well, both have acted in many indie films; “Capote” was an indie film.

GS I should ask what makes a film an indie film.

BL An indie film usually doesn’t have a distribution deal when it starts shooting. The distribution, of a studio film, is in place before filming begins. Sony Classics bought the distribution rights to “Capote,” after they finished shooting it.

GS Usually, an indie film is grittier than, say, “Capote” or “Devil.”

BL I think what you mean is film versus digital. “Devil” is 100% digital, shot using the “Panavision Genesis System.” This was a revelation for me.

Before I started producing, I was an artist in post-production. I was a telecine colorist. I transferred film to video, for 15 years.

I have high standards for cinematic imagery. I couldn’t believe how great the digital looked. There are only a couple of points in “Devil” where I can tell it’s not film.

GS I couldn’t tell anywhere. I would never have guessed. Digital has come a long way.

BL Yes.

GS Neal Gumpel (above), the screenwriter, mentioned you’re producing some of his work.

BL Yes, Neal is a brilliant screenwriter, but admits to knowing nothing about movies or Hollywood. Before I met him, face-to-face, I thought he might be pulling my leg, but not a chance.

A mutual friend introduced Neal and I. Our friend told me a pile of stories about Neal. I didn’t believe the stories.

For a while, Neal lived in Alameda, California, near San Francisco. He’d drive to Hollywood, as necessary, and stay at my house for a few days. During this time, I discovered every story I heard about Neal was true and when he talks about his life, he tones it down.

GS When I interviewed Neal, it was sometimes as hard as pulling teeth to get him to come clean about his life.

BL Every story told about Neal or Neal and his pal, AJ Benza, is true. Neal is a magnet for insane events. He has voodoo magnet magic that draws weird, crazy events to him.

Neal and his wife, Helen, were trying to sublet their apartment in New York City, about 15 years ago. No one wants the sublet. Then Jim Sheridan, the movie producer, pays cash for the sublet, for his daughter, and offers to buy a screenplay Neal had yet to write.

Now, that’s a bizarre story, which is unbelievable, but one hundred per cent true.

GS That’s exactly how his life plays out.

BL Yes that script was “Lucky Men.” Neal is a natural. He has a natural gift to write for the screen. Neal is one of the smartest people I know, yet his approach to screenwriting is instinctive, not studied or formulaic.

When I first read a script, by Gumpel, I thought, oh my gawd, this is it. This is what I’ve been looking for, all these years. As a movie producer, I read so many terrible scripts that when I come across quality work, such as a Gumpel script, I celebrate.

Gumpel can write. He can conjure ideas and put his ideas on paper. He’s not a technical screenwriter, who reeks of film school. Neal sits down and outflows a great screenplay,

GS It falls out of his head.

BL Yes; the McKee Method and the Sid Field Method are alien to him. Gumpel doesn’t follow a formula; he didn’t learn his art in film school. He sits down, with a yellow pad or, maybe, he dictates to Helen, and ideas, characters and plot flow.

What Jim Sheridan bought was a stream of consciousness Neal dictated to Helen. She wrote it on a yellow pad and left the pad on the coffee table. When Sheridan read the story, he realized Neal is a genius writer.

GS An insane Gumpel event happened when Sheridan bought him to Hollywood.

BL Right, Sheridan shows Neal around and introduces him to everyone. “Here’s my new writer,” Sheridan says. “He wrote my next movie. Neal is a down-to-earth man, with enormous insight and the ability to write about what he sees.”

End of one day, Sheridan and Gumpel are at Icon, owned by Mel Gibson. I know Gibson, who swears what I’m about to tell you is true. This is classic Neal Gumpel.

After a meet and greet, with the executives, at Icon, Sheridan introduces Neal to Mel Gibson. They talk, for a long while. At the end, Gumpel stands up, reaches his hand out and says, “Thank you very much Mr. Costner, I appreciate your time.”

I didn’t invent this story. I’m not pulling your leg. This is the life of Neal Gumpel; he had no idea to whom he was talking.

His life is full of such events. A script based on the honest life of Neal Gumpel would not sell. It’s unbelievable, stranger, in a good way, than fiction.

GS Are you producing “Uncoupled,” the Gumpel script.

BL Yes, it too has a basis in fact. In “Uncoupled,” two men meet on a commuter train into New York City. They get to know each other and find out alimony is taking a heavy toll on each of them. They devise a scheme to end paying their ex-wives.

About 15 years ago, Neal decided, for some reason, Helen should marry his rich friend. He schemed to fix them up and almost did. He and Helen divorced, but she didn’t marry his friend, she remarried Neal.

GS The life of Neal Gumpel is unusual.

BL After their divorce, Neal and Helen got back together, but not married. Then Neal found out one of his daughters, from his first marriage, needed emergency surgery. He had no money or medical insurance.

Helen had insurance. They remarried to save his daughter. It turns out his daughter didn’t need surgery, but they stayed married.

GS I think that’s love.

BL In the world of Neal Gumpel, love is the word for it, but maybe not everywhere.

Back to “Uncoupled,” Neal originally pitched the idea, not the script, about ten years ago, to Bob Cooper. At the time, Cooper was President of DreamWorks. Cooper bought the idea, on the spot, and cut Neal a cheque to write the script.

The script languished at DreamWorks. Cooper left the company and there were limp tries to sell the script to another studio, but nothing panned out. When a chance to recover the script appeared, Neal rescued it.

Neal updated the script. We re-worked the plot a bit. Now, “Uncoupled” is circulating again and its prospects are great.

GS Isn’t the script a twist on an old movie.

BL “Uncoupled” is a variation on a 1950 move, “Strangers on a Train,” directed by Alfred Hitchcock and written by Raymond Chandler. Neal had not seen the movie, nor had he heard of the movie. The idea was unique to him, but the twist of a twist, in the idea, had convinced Cooper of its potential for success.

GS I think Neal told me he has yet to see “Strangers on a Train.”

BL That’s Neal. Everyone that reads the script goes, “Oh my gawd, it’s a new take on “Strangers on a Train.” Gumpel says, “Yeah, that’s what I keep hearing, but I don’t know.” He still has not seen the movie.

The accidental overlap, of two men meeting on a train, is where the likeness ends. The rest of the story and script reveal that event in the life of Neal and Helen. It’s a true story.

GS The life of Neal Gumpel is less believable than fiction.

BL That’s it. Something I realized, after working in the movie business for a while, is truth is honestly stranger than fiction. When you get to a point where you understand how to create a story, you realize honest true-life doesn’t transfer into fiction, well. Thus, few believe the stories about Neal.

It makes sense, if you think about it. Stories are how we, humans, understand the world and learn to survive. We need to make sense of life, our environments, and stories are the most effective medium available.

Stories let us make sense of and order our world. When we’re children, nursery rhymes, such as Humpty-Dumpty, tell us we can hurt ourselves beyond repair and not even the King or the state can help save us. Hansel and Gretel directs children not to be too adventuresome.

All stories, songs, poems or screenplays, try to order the world. It happens the most pervasive forms of story, in the world, are American cinema and pop music. Although not as successfully, today, as a generation ago, America tries to order the world through its stories.

Stories rely on conventions and rules. Sometimes a writer can subvert the rules. Other times she or he can’t subvert the rules.

In the end, what you have are rules. We know the rules. When we write, grammar rules, and when we talk, speech rules are in control.

One rule, in cinema, is truth or factuality doesn’t necessarily count. Message is everything, especially when implicit. The old bio-movies, of George Gershwin or Alexander Graham Bell, built on a little fact and much fiction to find enormous success.

Back to Neal Gumpel. Most factual stories about Neal don’t follow the rules. What husband tries to marry-off his ex-supermodel wife to a friend? The life of Neal Gumpel is unconventional and, as fiction, isn’t believable because it doesn’t play by the rules.

When Neal writes about events in his life, he has to make those events accessible. This means he must change or add some facts and much fiction. He had to fictionalize the current version of “Uncoupled” as the true, factual version was not believable.

The original version, of the screenplay, was spectacular, but not a movie. It needed more balance and stronger female characters. To create a Hollywood version, of truth, Neal had to make it less true.

GS When I read “Uncoupled,” I wondered why the “Douglas” character wasn’t harder and more scheming. Why wasn’t “Douglas” more like Gordon Gekko, in the movie “Wall Street”?

BL I think that was what Neal had in mind, a Gordon Gekko character, although he didn’t know it. Yet, he didn’t want to distract from several key parts of the story. If “Douglas” is too mean, the character diverts too much audience attention from other characters, which also have much appeal to the viewer.

Let’s back up, a bit, for clarification. “Douglas” and “Michael” meet on a commuter train to New York City. “Douglas” is paying alimony to his ex-wife “Barbara,” an art collector. “Michael” is paying alimony to his ex-wife, “Caroline,” who uses the money to go to school.

Riding the train, into and out of New York City every day, “Douglas” and “Michael” get to know each other. A scheme emerges to end the alimony payments by marrying off their ex-wives, to each other. Neal was wise not to have the scheme involve murdering the ex-wives; the remarriage is a stroke of genius.

A key part, of the script, is how “Barbara” comes to realize why “Douglas” chose “Michael” to marry her. “Douglas” sees himself in “Michael”; what he might have been, not what he became. Also important, to the story, is how “Douglas” realizes he sees “Barbara” in “Caroline.” In turn, “Caroline” sees “Douglas” as a more confident and successful version of “Michael.”

Make “Douglas” too hard or harsh, a Gordon Gekko, and he can’t let go of his ego. This quartet of characters must be reasonably believable. The balance, the symmetry, among the characters is important to the story.

The symmetry is younger man attracted to older woman and older woman attracted a younger man. The result is a criss-cross. This criss-cross carries the storyline forward, plays by the rules and holds viewer interest.

GS How did this twist on a twist arise?

BL It came from rewatching “Strangers on a Train.” I couldn't shake loose from the term, criss-cross. A song melody often sticks in the mind, well this term stuck the same way, with me.

I said to Neal, “You know what we need to do? We need to bring a sort of symmetry, a criss-cross dynamic to this script. We need to have things connecting. We need to have “Douglas” and “Caroline” connecting. We need to have these parallel connections. We need to highlight these connections, which exist, in the script. We need to explain why the criss-cross takes place.

Neal grasped the criss-cross, right off. We talked about how it might work and Neal went off to write. A few weeks later the perfectly revised script arrives.

In this sense, Neal is an unusual screenwriter. Typically, a writer passes a script and treats what he or she dumps as their child. They won’t change a comma, without a fight.

Neal pumps out the first version and asks what needs redoing. He’s open-minded about changes; he sees rewrites as acts of creativity. Few writers are as open as Neal Gumpel.

GS Can you give us another example of Neal and rewrites.

BL Sure, when I first hooked-up with Neal, it was for a script called “Pushing Daisy.” I bought that screenplay outright, which is rare. I still own it.

I’m making a movie out of “Pushing Daisy.” It’s a spectacular script, with an exceptional role for a young woman. The right actor, at the right time and “Pushing Daisy” is a great movie: funny, sexy, sweet.

When I bought “Pushing Daisy,” I attached it to a director, Nigel Dick. He’s also an actor, but mostly known for directing music videos. “Nickelback: the videos” is most well known among his recent videos.

Nigel is a wonderful man, but the single most anally retentive perfectionist I’ve met. When I optioned “Pushing Daisy,” I sent the script to Nigel. He sent back pages of changes he wanted made. I think twice, as I don’t know Neal, well, at this point; I had only met him at Mel’s Diner, on Sunset Boulevard, when we completed the deal for his script.

I sent the notes to Neal, expecting who knows what. Neal and I talked, on the phone, about the changes Nigel wanted. Two or three weeks later, I get the changed script from Neal.

I send the new draft to Nigel. I’m expecting many more pages of changes. There’s no response and now I’m worried.

Two or three days later, Nigel calls me on an unrelated matter. I ask about more changes for the script, of “Pushing Daisy.” Nigel says, “No notes, he did everything I asked him to do, it’s perfect.”

That was a forerunner of working with Neal. This is an incredible advantage to me, as a producer. It’s too rare.

It’s a given that all good writers are insane and ego-driven. Maybe this is why they can write. I have to deal with whatever brand of eccentricity or insanity my writers choose.

Gumpel is no different. Yet, he works in an open-minded way. The word comes easy to Neal and he likes to write and rewrite, I guess. Neal is incredibly prolific.

If I give him a note, which is specific, he writes, without problem. If I’m too abstract, if I say, “This isn’t working,” Neal does nothing. If I say, “I don’t understand why such and such is happening,” he adds and rewrites it, well, and keeps going until I understand.

GS Back to Sidney Lumet (above, with Linse), for a moment. Do you think “The Verdict,” which he directed, in 1982, is his best movie?

BL I saw “The Verdict” in its theatre run, in early 1983 and it changed me. I was in film school when I saw “The Verdict.” I thought I knew all there was to know about making movies. Lumet brought me back to reality.

I walked out, of the theatre, on to the street, after seeing “The Verdict,” realizing it was a perfect movie. I turned around, bought another ticket, went back in to watch it again. I couldn’t believe “The Verdict.”

Lumet is my favourite director, of all-time. Now, when I had opportunity to work, with him, he was working for me, I hired him. That was a rush.

I was nervous about hiring him. What if we don’t or can’t get along, I'm in a fine fix. I guess I didn’t care. I wanted to watch him work, especially on my movie.

GS He sells tickets.

BL That’s for sure, but if he had hated me, I’d be all right with it. He couldn’t keep me off the set. Like me or not, I’d go and watch him work, every day, and I did.

In those four months, watching Lumet, I learned more than four years in film school. Heck, I learned more than in my 15 years, on-the-job, in Hollywood. Just sitting next to him or talking to him, I felt as if some of his knowledge and skill seeped into me.

GS He’s a rare man. At 85, he has movie projects, down the road, as far as the eye can see. It’s unbelievable.

BL He has endless stamina. I couldn’t physically keep up with Lumet, when we were shooting on location, especially when it was hot. His age never shows, when he’s working.

Granted, I’m so fare-skinned, I’m translucent. I can’t handle the sun and heat. I had to sit down and pour a bottle of water over my head to keep from fainting. All the while, Lumet continued to run around from the camera to the actors, back and forth, while I sat down, trying not to faint.

GS He’s unbelievable.

BL He’s twice my age, to boot, exactly twice my age, at the time.

GS You believe “The Verdict” is a perfect movie.

BL It is, I think, framed more effectively than any movie I’ve seen. Lumet picked the right emphasis and the cinematography is superb. The actors gave career-defining performances, too.

GS Only 43 days to shoot a movie that runs almost two hours.

BL It was a studio film, with a bigger budget and bigger stars, such as Newman and Jack Warden. James Mason was superb as the opposing council, too, as was Charlotte Rampling as the duplicitous girlfriend of the Newman character.

Mostly, the effectiveness of “The Verdict” is the Lumet style. He came up in live television. He learned how to work quickly and effectively.

GS Jack Benny once said, “My best ad-libs are the ones I rehearse the most.” I read Lumet rehearses his movies.

BL I’m sure his fondness for rehearsals comes from his days directing live theatre. Lumet rehearses, whereas most movie directors don’t. He rents a large space, a ballroom, say, and blocks out the floor to match movie locations; he builds the sets, in this location, too. Lumet is thorough.

Then he rehearses the actors, thoroughly. Everybody becomes familiar with locations, sets, angles and so forth. When Lumet starts to shoot the film, everybody and everything is ready to go.

GS Preparation cuts costs or so it seems.

BL Yes, the best-prepared get the job done right, first time.

I think “The Verdict” is as good as a movie gets. No one can go through “The Verdict” and convince me the camera should move an inch to the left for this scene or a cut should come two frames before it does. This is a flawlessly built movie.

For me, “The Verdict” is a frame-perfect work of cinema. There are few such movies. “The Graduate,” directed by Mike Nichols, is a frame-perfect movie. So, too, is “Chinatown,” directed by Roman Polanski. Otherwise, I'm hard-pressed to name a perfectly framed movie.

I can’t gripe about these movies. Each, of these three movies, is a work of cinematic art. Even movies, in my personal top ten, I find somehow flawed, but not these three. There’s no need to change a single frame in any of these three movies.

GS Lumet, in “The Verdict,” carries the audience along, well.

BL Keep in mind I was in film school, when “The Verdict” released. I was in a headspace where I over-analyzed every movie I saw. I could see the duct tape and the screws that held the movie together.

I was critical. I would see a Spielberg movie and think, “Why does he movie the camera there?” I had an opinion about everything, when I was at film school. I believed I could tell Spielberg how to direct.

Then, I walked out of “The Verdict” not having much to say, not a word to say, in fact. Lumet scooped me up from the beginning, carried me along, messed me up and dropped me off on the sidewalk, outside the theatre.

GS And cleaned off its hands and walked back in.

BL Yeah, “Ok we’re done, see you later.” I think, “No, no, no, wait a minute. Give me another ticket. How’d he do that?”

I was not aware of the Lumet style before “The Verdict.” I watched “The Verdict,” again, thinking Lumet must not have any style. When I sat through it for a second time, I looked for the flaws. There were none. I realized “The Verdict” is an incredibly stylized movie.

GS What’s the Lumet style?

BL The Lumet style is to always direct or act in service of the story. He’s never there for the sake of style, alone, or his ego. That’s what makes “The Verdict” a frame-perfect movie: direction to service the story makes Lumet a great director.

If you analyse “The Verdict,” you see all the stylized work he’s doing. If you know cinema, you can see deeper into it. If you don’t know cinema, you thoroughly enjoy what Lumet is doing, but on another level.

GS What do you think is his most important technique?

BL Focal length is the Lumet signature. Focal length in full service of the story is how he works. Lumet uses focal length and camera lenses better than does any director.

Watch “The Verdict,” closely, and you see what’s he’s doing, stylistically, how he uses focal length. The focal lengths, of the camera lens, change slowly, throughout the movie. Maybe he’ll start by using a telephoto lens, with the camera further away from the subject; slowly, the camera creeps in on the actors.

The summation, by the Paul Newman character, near the end of “The Verdict,” is a solid example of this style. As Newman begins the summation, we see the jury, in front, and the gallery, in the back. At the end, of the summation, Newman is alone in the frame.

GS Good message, in a camera lens: we’re all, together, but someone has to lead.

TH “Prince of the City,” which Lumet directed, also offers examples of this technique. “The Prince” begins, slowly, with a telephoto lens and the camera faraway from the actors. By the end, of the movie, Lumet moves to wide-angle lenses and the cameras a foot away from the actors.

Lumet has led the audience into a sense of suffocation, in “Prince of the City.” This is how the main character feels. Lumet makes the point, of the movie, fully, but subtly.

For Lumet, the camera and its stylization support the story. He makes the themes visceral, for audiences, through camera use. The brain understands and tells the mind.

Lumet doesn’t care if he’s obvious or not. He doesn’t have to whip the camera around, as does Scorsese, to confirm he knows his trade. Lumet always says, “What can I do, what language of cinema can I use that will convey what I need to convey what is happening in the story right now.”

GS Lumet is a remarkable director.

BL Yes and it’s not that he doesn't have an ego. It's that he doesn't let his ego interfere, with telling a story. He never creates a frame only to show he can do it or to flatter himself. All that Lumet does services the story.

GS There are many one-shots, scenes where a single actor is framed, alone, in both "The Verdict" and "Prince of the City." This technique puts much emphasis on editing.

BL In part, it’s for editing, but this is the Lumet style. He stresses story and acting more than flashiness. More often than not, Lumet points the camera at the actor and rolls.

He likes to start, with a wide-angle shot, and move in on the actor. The result is a “one shot,” naturally flowing from a more general perspective. Always, though, this technique is to service the story.

GS Lumet puts much effort into scripting a story he can work, effectively.

BL Again, yes, but it doesn’t always work out as planned. Lumet is the first to admit he’s done a few movies, from poor scripts, because he has bills to pay. Not all Lumet movies are A-list, but his worst movies are worthy of attention. Even his worst movies show his superior craft ability. So, from the worst Lumet movie, anyone can learn much about good film directing

GS You’re taking the auteur approach.

BL I guess so, but my point is that understanding why his bad movies are bad is important. Understanding why Lumet made a poor movie may be more important than knowing why he made a great movie. There’s much to learn in mistakes.

“Guilty as Sin,” a 1993 movie Lumet directed, is a good example of his bad movies. Don Johnson and Rebecca De Mornay weren’t the actors for “Guilty as Sin.” They were relatively popular actors, in 1993. Johnson was still riding the wave of Miami Vice.” De Mornay had starred in “The Hand that Rocks the Cradle,” in 1992.

“Guilty as Sin” was a debacle. Still, I watch it and learn. I see what Lumet tried to do, despite the actors, although Jack Warden and Luis Guzman were solid.

GS This is one of his mortgage movies.

BL Lumet won’t name his mortgage movies, but Guilty as Sin” is clearly a mortgage movie for someone.

GS I started to watch “Guilty as Sin,” but couldn’t take either lead actor.

BL Yeah, it was painful. I think “A Stranger among Us,” in 1992, was another Lumet mortgage movie. Melanie Griffith as a detective looking into a murder, in the Hasidic community, is a stretch. Still, if you’re a student of Lumet, you can watch these mortgage movies and learn much from them.

What I’m saying is you can watch the best movies of top directors and learn nothing. Watch the worst movies, by Lumet, and you learn much. This is what makes Lumet important.

By the way, James Gandolfini portrayed “Tony Baldessari,” a gangster, in “Guilty as Sin.” He was starting out and the role was good for him. Lumet used Gandolfini, again, in “Night Falls on Manhattan”; he portrayed “Joey Allegretto.”

“Night” is an underappreciated Lumet film. He made a good movie, the right way. Andy Garcia was superb, in the lead, as “Sean Casey,” of all names for him.

GS Andy Garcia portraying a character named “Sean Casey” ruined that movie for me.

BL A key scene, in “Night Falls,” starts with the camera tight on the “Casey” character, seated in an office. The District Attorney tells him he has no way out. As the scene moves along, someone enters the frame from the left. Then someone enters from the right. Slowly, Lumet places “Casey” in a visual box, which is where the story has him.

There wasn’t a cut, in the scene. The camera worked faultlessly for the story. Lumet is one among a few directors who can pull off this type of shot.

That’s what Lumet does best. I can learn the most from his lesser movies. I can’t say the same for every director.

GS Neal Gumpel said you had him watch Lumet and he learned a lot.

BL I made Neal watch “The Verdict.” He hadn’t seen it, if you can imagine. It blew him away, but he couldn’t explain why.

This is pure Neal Gumpel. He can’t sit down and say, “Ok, you know how Lumet did this, this, that and the other thing?” Neal is visceral; he knows when it’s right, but doesn't express why.

Neal is like most media consumers. He grew up in a media world. He, like everybody else, knows the grammar.

It’s much the same way we know how to speak and write. As children, we test our language skills. Does this word work? We learn rote skills, such as ran, not runned, is the past tense of run.

As media consumers, we test what we learn. Does this frame accurately predict a later frame? We’re all right when a murderer gets away, with the crime, if the victim had committed a wicked crime, first: a wife, physically abused for years by her spouse, kills him, but doesn’t go to jail. As our predictions grow increasingly accurate, we come to understand media content and an intuitive language for cinema develops.

GS An intuition develops to make storytelling easier for media content creators and consumers.

BL Yes, and that’s where Neal lives. He hears a song. He finds it sad, but doesn’t realize it’s probably in a minor key and that’s a large part of what creates his emotion, of sadness. We don’t need to know the technique to react properly.

Neal's lucky. He has radar more fine-tuned then does the average woman or man. He sees “The Verdict,” subconsciously analysing and storing it. Since Neal can also write well, he expresses his intuition better than someone who went to film school, but not the formalities, such as camera angles or staging.

I don’t think it’s anything mystical. Some men or women have it and most of us don’t. I know a woman who learned Japanese in six months, reading, writing and speaking. I still have difficulty with English.

Neal has a unique ability. He claims to know nothing about media and not to care. Yet, if you watch television, with him, he gets the subtle points, of every content item, which others do not. If you work him, he can tell you about it. Otherwise, he stores for use at a later time.

GS Neal Gumpel is exceptional. Do you know his pal, AJ Benza?

BL Yes, and like Neal, AJ is crazy in good way. They’re both afraid of ghosts and think ghosts are going to get them. AJ is afraid of dew-covered grass. Good writers are insane, in a good way.

GS Do you have a Neal and AJ story?

BL Who doesn’t have a Neal and AJ story? They get into the craziest messes. No one believes what happens when AJ and Neal get together.

For a while, Neal lived in Alameda, California, about five hours north of Hollywood. As needed, he drove to Hollywood. Sometimes he stayed with me; other times, he stayed at an apartment AJ rented.

Neal tells AJ he’s coming to Hollywood for a few days. AJ says, “Great! I’m off to New York City for a week. You’ll have the apartment to yourself and you can work, peacefully.”

Neal comes to Hollywood, stays at the home of AJ, gets his work done and leaves. Before he leaves, though, he decides to play a trick on AJ. Neal finds a mannequin, somewhere, and hides it in the linen closest, in the bathroom.

When AJ comes home, Neal knows he’ll take a shower. When AJ goes for a towel, he’ll open the linen closest, see the mannequin and freak out. Neal is giddy about the prospects of scaring the poop out of AJ.

As it turns out, AJ is gone much longer than expected. Neal arrives, for a short stay, the same day AJ returns. Neal has forgotten about the mannequin. He, Neal, takes a shower, opens the linen closest, out falls the mannequin. Neal screams, as a banshee and faints from fright, on the bathroom floor.

AJ hears the scream and the thump of Neal hitting the bathroom floor, hard. He races to the bathroom, knocking over furniture along the way. AJ finds Neal on the floor, bleeding profusely from the head.

Then, AJ notices the mannequin. He starts screaming. Neal is out cold, on the floor, and he can’t enjoy the moment.

A neighbour calls the 911. The police think AJ tried to kill Neal. The apartment looks like they had a knock-down and drag-it-out fight, but no one can figure how the mannequin fits the scenario.

This, no kidding, is a typical day in the lives of Neal and AJ. Who believes what they do, when they’re not writing. If I tried to sell the day-to-day life, of Neal and AJ, as fiction, no studio executive would buy it.

GS Tim Hallinan, the novelist, said he writes, without a plan, and likes to discover where the characters take him. He thinks a screenplay needs a plan. What’s your take on this distinction?

BL A script needs a plan. The writer needs to know where she or he is going, when they start. The reason may not be what you first think.

The script is a plan others use to create a work of art, a film. Directors, actors, cinematographers and set designers, for example, base their creativity on the script. A screenplay doesn’t stand alone, as a work of art, as might a novel. Getting a script to the screen is a collaboration of many arts and artists.

The screenplay depends on the imagination of other creative arts. The screenplay is a muse for a costume or set designer. Contributions from other creative talent make the script work.

GS Yes, you can tell that, can’t you?

BL Also, if the basic plan, the script, has flaws, the other creative talent can’t do their best. A bad script doesn’t always bring out the best in directors or actors. The point is the basic plan, the script, must be good.

The opposite is true and maybe more often. A great script fails to deliver because of too many rewrites, a distracted director or poor cinematography. Maybe it’s a mortgage movie for everyone involved.

If I find a good script or a great idea, pitched by a good screenwriter, I “option” it and put it into development. In development, I attach a director, maybe actors and other creative talent. I spend much time looking for money. If a script isn’t a good plan, it can’t hope to find backers or A-list performers.

GS Yes, Neal talks endless about the pitfalls and profits of being in development.

TH In Hollywood, there are writers, for example, who are always in development. They write decent scripts and get “options,” but their work languishes. While in development, they’re paid, but the script isn’t strong enough, they can’t or don’t supply a good plan for their great idea.

This adds an enormous amount of money to the cost of a movie. A producer might “option” ten scripts, but only one makes it to the screen. That one film carries the development costs of the nine scripts, which are gathering dust on the desk of the producer.

GS Can you sense when a movie is a hit, while you’re making it?

BL As Lumet told me, often, “You never know about a movie. You think you made the best movie, ever,” he says. “Then no one goes to see it. This is not unusual.”

GS How did you feel about “Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead”?

BL “Devil” opened at film festivals, to good reviews, but talk is cheap, especially at junket-events, where food and drink are free and plentiful. I had to hold off, on a final decision, until “Devil” opened to ticket buyers.

GS Good reviews don’t always sell tickets.

BL That’s the truth. I sat in a theatre, in New York City, when “Devil” went public. My jaw hung open during the showing. I couldn’t believe the audience reaction. During some scenes, people covered their eyes or curled up into balls, in their seats. For other scenes, they yelled at the screen. I could not believe the reaction.

After the showing, I scampered outside to hear what people had to say about “Devil.” Many people were laughing, nervously, when they came out. For many, in the audience, it was as if they’d seen a horror movie.

I felt great. A year and one-half of my life spent making a film audiences enjoyed. When I started “Devil,” I wondered if the investment, of my life, in the movie, would work out. It did.

with Arianna Huffington (left);

with Ethan Hawke and Philip Seymour Hoffman (right)

GS You see the world through a specific lens, not to pun. You focus on stories and storylines. Do I read you correctly?

BL Stories and storytelling are a hobby, of sorts, for me. I guess the viewpoint probably came about through osmosis. I can tell it’s finally seeping into my consciousness, helping me make more sense of daily life.

GS I would think it common among moviemakers.

BL Not so, few movie writers, directors or producers, for example, think of their livelihood as something essential to the species. Not many women and men, in the film business, consciously consider this idea. They don’t realize they’re engaged in a pursuit necessary for human survival; I’m not exaggerating.

GS What do they think they’re doing?

BL Hard to say, exactly, but few of them think of it as more than making money or winning fame. Men and women, who tell stories, are providing an essential tool for our survival. Every one of us, not only those who make movies, but other storytellers, strive to make sense of life: storytelling is making sense of the world.

Why did this happen? How did that happen? At root, storytelling is how we learn to order the world; a sense of order reduces apprehension about the future.

The first recorded story comes from Sumeria. The story is about Gilgamesh; he’s two-thirds gawd and one-third human. His story is the story of the origins of the Sumerian people.

The written version, of the story of Gilgamesh, the story of the Sumerians, is about 6,000 years old and we continue to read it. You’d think people in Hollywood would take it a little more seriously than they do, given the oldest story remains important. Well, they don’t and maybe a handful realize what they do, for a living, is recreate such stories.

GS About the story, is there much difference between Sumeria, 3000 BCE, and Hollywood 2001 ACE?

BL Except for technology and complexity, there’s not much difference. You can look at any story form and understand how, as a species, we order the world around us: leaders, followers; struggle to survive; lust, love and loss. Storytelling and the stories told seem a species-specific act.

GS The order is in the mind and the story is an expression of what we think.

BL Yes, it’s what we think and the mind decides how we think. As a species, our minds have changed little, over time. Go back to Aristotle: his “Poetics,” written 2400 years ago, is the best guide to watching movies or reading novels, today.

There’s a good, modern example in the movie “No Country for Old Men.” The storyline seems simple. In 1980, a working-class man stumbles on the aftermath of a shootout among drug dealers. In the carnage, he finds two million dollars and decides to keep it. This sets a sociopathic hired killer after him.

There’s an age-old message in the story: strike while the iron is hot. Here is two million dollars, ill-gotten gains, for the taking. The temptation to snatch such easily available resources is hard to resist.

Another, deeper, messages is that each generation faces new tests. The last generation passed its tests, but old solutions may not work well against new challenges. A new generation means news ways to confront new challenges and pass new tests.

In the book, “No Country for Old Men,” written by Cormac McCarthy, “Moss,” who finds the money, and “Chigurh,” the hired killer, are Vietnam veterans. There’s a sense of a new world, where memories of Vietnam and its resulting entitlements are current; 9/11 and its reduced entitlements is unimaginable.

The new evil, which Sheriff Bell confronts, is a post-Vietnam evil. Bell can’t understand the evil. If he can’t understand the evil, how can he fight it?

Ethan Coen and Joel Coen produced and directed the movie. They also scripted an adaptation from the Cormac McCarthy novel. The movie caused much discussion. Did it work? Was the movie, as a story, faithful to the novel or not? Must a movie be faithful to the novel?

The Coens are among my favourite moviemakers. I was eager to see “No Country.” I expected to love the movie. I didn’t like it, thinking "No Country" confusing, from a storytelling perspective.

The script, which up-ended some movie conventions, troubled many viewers. Other viewers liked the movie. “No Country for Old Men” split opinion, which may be good, and it won many awards.

GS What did the Coens not do right?

BL After watching the movie, I had to read the book. As it turns out, the book is from the perspective of the sheriff, “Ed Tom Bell.” Tommy Lee Jones portrayed “Bell,” in the movie.

The movie starts on a narration, by “Bell,” in 1980. In the novel, the narration spreads throughout the story. When you read the novel, it’s one hundred per cent through the eyes and awareness of the sheriff, but the movie shifts the perspective.

The Coens didn’t build the movie around the sheriff. They focused on “Moss” and “Chigurh.” These characters reside outside a conventional American moral context, where a seemingly uncontrolled, opportunistic evil exists.

In the movie, the sheriff, who understands in a pre-Vietnam way, confronts a post-Vietnam world. He doesn’t understand the new world. His moral map seems outdated.

The first part, of “No Country,” is a conventional Hollywood cat and mouse story. “Moss” is a standard hero. “Chigurh” is an ostensibly standard villain. “No Country,” focuses on the new world through “Moss” and “Chigurh” and this part of the movie works, well.

Then someone, “Chigurh,” perhaps, or others related to the drug money, murder “Moss,” off-screen. Viewers learn about the murder. They don’t see it happen.

Suddenly the movie shifts to the sheriff. A large portion, of the audience, I suspect, went adrift with this transition. Maybe not, but I strongly suspect so.

It’s unconventional to kill a main character, off-screen and without warning, in the middle of a movie, subversively unconventional and possibility good movie making. The more urbane viewers understood the point, but not everybody. Many viewers felt led down the garden path and abandoned.

GS Let’s see if I follow you. Killing “Moss” off-screen, in the middle, of the movie, when he’s the central character, is conventionally unconventional. This is always good, but it left many viewers confused. Then the Coens shift back to the story in the novel, which is strictly conventional.

BL In a sense, the Coens changed canoes in midstream, from film to book two-thirds into the movie. This makes the movie, “No Country for Old Men,” two movies. One movie goes on for the first two-thirds and the other movie comprises the last third of the move.

GS Intricate, for sure; when I re-watched the movie, I saw exactly what you point out. Does the shift change the core message, of the book?

BL I think so, as the world changes, new kinds of evil are harder to understand. The sheriff is old school and may not know what he faces, that is, a sociopath, in the new world. Still, many viewers did not get this message and it's unfortunate.

There are conventions that allow telling the viewer what’s to come. Viewers rely on such foreshadowing. Otherwise, plot turns or events, such as killing a central character off-screen, may seem out of left field.

GS I guess sophisticated viewers vote for awards.

BL Movies involve many arts. Javier Bardem was superb and earned his awards. “No Country for Old Men,” for me, was a fair movie. The story, in the movie, didn’t build a full picture and the point was off mark, but still a decent movie.

I would’ve enjoyed the film more, if the Coens had stuck closer to the theme of the novel. This isn’t always the case, for movies, or necessary. “Blade Runner,” for example, is much more interesting than the book, “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep,” by Philip K. Dick, on which it’s based.

What the Coens did, in “No Country for Old Men,” was set up conventional expectations, in the audience, and deny fulfillment of those expectations. In a sense, the Coens abandoned the audience. The Coens are brilliant. I’m sure they knew what they were doing. Yet, I fear they asked more from the audience than many, in the audience, could give.

My sense is the novel, “No Country for Old Men,” had the potential to rank alongside “The Graduate” and “The Verdict.” Artists decide and I’m not sure the Coens made enough “right” decisions, for this move, to realize its full potential. “No Country” is an award-winning movie. Yet, is it the best movie it might have been?

GS Thanks, Brian.

BL You're welcome.

Click here for a list of all Grub Street Interviews.

Interview edited and condensed for publication.

dr george pollard is a Sociometrician and Social Psychologist at Carleton University, in Ottawa, where he currently conducts research and seminars on "Media and Truth," Social Psychology of Pop Culture and Entertainment as well as umbrella repair.

- 96 Words

- Eileen Cook

- Larry Glick!!!

- Stoking the Imagination

- Jerry Williams

- Brian Linse

- Edward R Murrow

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Regarding Broccoli

- F for Sex Scandals

- Count in a Box

- Sjef Frenken

- Well, Well

- Rooting for the Underdog

- Reading

- Jennifer Flaten

- Bic Pens for Her

- My Head as a Cookie

- Campaign Stop

- M Alan Roberts

- Tiny Teachers

- Doing Time for No Good

- Truth Unbound

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Spam

- The Last DJ

- Walking

- Streeter Click

- Stand-up Comic

- Steve Allen

- Leroy Jones Top 40

- JR Hafer

- Life as a Classroom

- Habit-forming

- Scott Muni

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- A Little Singing

- The Ole Barbershop

- A Mother Knows

- Jane Doe

- Guitar Woods

- US Election 2016

- A Coffee Mug

- M Adam Roberts

- My Eraser

- Lessons in the Park

- No Quitter

- Ricardo Teixeira

- There is a Light

- The Future

- The Unicorn