Stoking the Imagination

dr george pollard

Jack Benny, left, and Fred Allen square off in the most famous media feud of all time. Wives, Mary Livingstone, left, and Portland Hoffa, right, hold the suit coats of the competitors.

Introduction

For author Mel Simons, Old-time Radio (OTR) is television without pictures. “The mind of the listener, the imagination,” he says, “is the picture tube. The mind paints pictures for you. That’s what radio was until the 1950s. Then it adopted a local focus, relying on disc jockeys (DJ), music and news.” [1]

Capturing the imagination using audio began in the late 1800s. Live transmissions from vaudeville theatres were possible. Although not widely used, anyone with a telephone might call to hear a show. Later, vaudeville shows recorded to cylinders and, eventually, discs, which sold through the mail.

Vaudeville acts adapted the visual parts of their shows for listening. “I’m Not Rappaport,” a popular vaudeville routine, from the 1890s, and the basis of the Broadway play and the movie, is a good example.

Harry: Hey, Rappaport, I haven't seen you in ages. How have you been?

Dick: I'm not Rappaport.

Harry: Rappaport, what happened to you? You used to be short and fat. Now you're a tall and skinny. How has this happened?

Dick: I’m not Rappaport.

Harry: Rappaport, you were bald, when I used to know you. Now you have a full head of hair. How has this happened?

Dick: I'm not Rappaport.

Harry: Rappaport, you used to be young, with a beard. Now, you're an old man, with a moustache and jowls. You got old, so fast.

Dick: I'm not Rappaport.

Harry: Rappaport, you used to be a cowardly little man. Now you're a big and imposing man. How has this happened?

Dick: I'm not Rappaport.

Harry: You changed your name, too.

“Rappaport” is as much for hearing as for seeing. It worked, well, recorded or sent over phone lines. Each listener imagined Rappaport, in his or her own way; each vision was correct.

Early radio took advantage of imagination and imagineering of vaudevillians in much the same way. “Radio is an engaging medium,” says Anthropologist, Dr. Charles Laughlin (above). [2] “Radio drama flexes the imagination, which made it warm, Dr. Marshall McLuhan said. Television is cool; it leaves little to the imagination.

“I watch my version, of the action, between my ears,” says Dr. Laughlin, “as I listen to radio drama. This makes radio much more exciting than television.” Radio demands active participation through the imagination; television wants passiveness: sit, watch and maybe listen.

Mel Simons on WBZ-AM

Many vaudeville performers moved to radio, with the ability to provoke the imagination. “By the early 1930s,” says Mel Simons (above), “Jack Benny, Eddie Cantor and Fred Allen attracted tens of millions of listeners to their shows.” Each listener imagined the 1925 Maxwell, driven by Benny, “Allen’s Alley” or the many daughters of Eddie Cantor, each in a slightly different way.

“Imagination is OTR,” says Bobb Lynes (below). “The writing and the voices are important, but imagination brought the writing and the voices together. It created a full picture. [3]

“The ‘Fat Man,’” Dr. Charles Laughlin says, “is about how voice evokes imagination. The show, focusing on a portly detective, relies on the voice of J. ‘Jack’ Scott Smart. He had perhaps the most distinctive voice on radio. You could always pick him out of a cast, such as when he part of the ‘Mighty Allen Art Players,’ on Fred Allen.

“Smart was the consummate radio actor,” says Dr. Laughlin. “His reading of the ‘Fat Man’ was glorious. Listening to Smart was as listening to a cello. His voice drew listeners into the story, his role and the show. The pictures he created remain with me to this day.”

“Listeners take part in OTR,” says Lynes. “Listening to characters, such as “Fibber McGee and Molly” or Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, we imagine them as our friends. We’re interested in what the radio characters do and say.

“We want to know all about them. We assume their height, weight and appearance. From the scripts, we make decisions about their likes and dislikes, favourite foods and quotidian habits. We infer they’re as interested in us as we are in them.”

Such intimate awareness increased familiarity. Listeners treated George Burns and Gracie Allen much the same as they treated neighbours, co-workers or friends. Radio characters showed up regularly, making the listener laugh or cry, revealing the latest gossip or helping them fall asleep.

“We allowed these auditory images to visit us at home,” says Lynes, “to sit in our living rooms, for half an hour a week. They never disappointed us.

“It was a magic trip, all those years ago. It’s a magical experience, today, too. Nothing beats Old-time Radio (OTR).”

Ken Meyer (above) hosted “Radio Classics” on WEEI-FM, in Boston, five days a week, for six years. “OTR is what listeners heard, routinely, on radio for thirty years. It survives because historians see its worth as a form of art. The Internet helps OTR find new listeners every day, as women and men look for alternative forms of good entertainment.

“Capturing the imagination knows no limits,” says Meyer. “Many people like to think the blind are excellent listeners to OTR, but that's not necessarily true. The great part of OTR was and is how you draw your own pictures.

“Everyone had his or her idea of what lies beyond the creaking door on ‘Inner Sanctum,’ a mystery and terror show that aired from 1941 to 1952. You can draw, for yourself, what Matt Dillon, on ‘Gunsmoke,’ looked like or Paladin on ‘Have Gun, Will Travel.’ Who is to say you’re wrong.

“You can't be wrong. When you heard the voice of William Conrad, on ‘Gunsmoke,’ you thought Matt Dillon was a man no one could beat, in any way; his authority was unquestioned. That was the beauty of what we call OTR. Each listener painted his or her own picture.”

Less is more on radio, writes Walter Kerr. The less full a canvas, Marshall McLuhan suggested, the more an audience must fill in. Listening to radio demands involvement.

Television offers a full image, a series of still photographs, stuck in time and space. The medium asks nothing of the viewer. The goal of television writing, acting and so forth is to discourage involvement. Passive viewing is inevitable.

“Many younger people discover OTR,” says Ken Meyer, “and are elated. Stroking the imagination is as old as our species, going back to stories, of great adventures, told around the campfire. Radio offers special rewards, especially to listeners with vivid imaginations.”

Dr. Laughlin says, “OTR is a distinct form of drama. The best OTR was the best radio.” Except for the ‘CBS Mystery Theatre,” radio drama, of all types, comedy, crime or soap opera, didn’t exist in the USA after 1962.

“This isn’t the case in the United Kingdom,” says Dr. Laughlin. “The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) continues to produce radio drama; our idea of OTR makes little sense in the UK.” “The British,” said Virginia Gregg, the actor, “know a good medium when they hear it.”

The era of OTR, says John Dunning, began Monday 15 November 1926. On this day NBC, the National Broadcasting Company, sent its first signal across the wires. Sixteen stations, stretching only to the Middle Western states, received the signal and content from NBC.

The first network show starred Joe Weber, Lew Fields and Will Rogers. Weber and Fields, vaudeville headliners, found humour in rowdy stereotype, mostly German, grounded in their Dutch heritage. Theire characters spoke in a heavy German dialect and edged on ethnocentric.

William Penn Adair Rogers had a slow, folksy style. A Cherokee, he claimed his relatives met the Mayflower when it arrived; he also claimed he never met anyone he didn’t like. In 1926, Rogers suggested it was good that Americans weren’t getting all the government they paid for.

In the early 1920s, there was little planning. Radio stations offered airtime to musicians, storytellers and others, free or at little cost. The goal of radio content, in the early days, was to sell receiver sets. Department stores often underwrote the costs of running a radio station.

An announcer, in formal dress, would introduce each performer. The studios resembled high-end living rooms. A grand piano might sit in the middle of the studio, atop it sat a lighted candelabra supposedly relieved the stress of broadcasting.

A performer would do what she or he wished, for as long as they wished. Between performances, the announcer might make a short sales pitch to drive the sale of radio receivers. Then he, it was usually he, introduced the next performer.

When advertisers became interested in radio, content conformed. Performances followed a schedule that fit the needs of advertisers; a show sponsored by La Palina cigars followed a show sponsored by Pepsodent or Rinso. The fifteen-minute time block was popular among radio advertisers.

Most vaudeville and theatre circuits passed through Chicago, in the 1920s. The city was talent rich and much radio content originated in Chicago. Many network shows grew from local shows on WGN-AM, WENR-AM or WMAQ-AM.

“The Smith Family,” starring Jim Jordon and Marion Driscoll, aired on WENR-AM in 1927. Adding a Chicago-based cartoonist, Donald Quinn, the show became “Smackout,” on WMAQ-AM, in 1931. Quinn took the show three steps farther, creating “Fibber McGee and Molly,” for the NBC Red Network, in 1935.

An early version of “Sam ‘n’ Henry” aired on WENR-AM, in 1925. It morphed into “Amos ‘n’ Andy,” airing on WGN-AM, for two years. WMAQ-AM then aired the show for 18 months before it moved to the NBC Blue Network, in 1929.

A single NBC network aired shows from New York City, in 1926. The main network split on 1 January 1927. The Red Network fed from WEAF-AM, in Newark, New Jersey; its shows mostly sponsored. The Blue Network fed from WJZ-AM, in New York City; its shows mostly unsponsored.

To cover the western and pacific states, NBC launched the Orange Network on 5 April 1927; it aired content from the Red Network through KPO-AM, in San Francisco. On 18 October 1931, NBC launched the Gold Network to air its Blue Network content in the western and pacific states of the USA.

Arthur Judson, a talent agent in New York City, formed United Independent Broadcasters (UIB) on 21 January 1927. After many name changes and financial difficulties, UIB became the “Columbia Broadcasting System,” now CBS. Judson left the network when a young Wharton School graduate, William S. Paley, took over on 25 September 1927; he bought 50.3% of the company from the Levy Brothers, his in-laws, who owned WCAU-AM, in Philadelphia.

NBC, led by David Sarnoff, focused on technology. “In the early days,” Mel Simons says, “no one knew exactly how to air shows. A storyteller might simply talk into a microphone, but what about a comedian that needed audience response.

“When Eddie Cantor came to radio, in 1931, he wanted a live audience. Between him and the audience, the technicians placed a glass curtain. The purpose of the curtain was to eliminate audience reaction noise, picked up by the microphones.

“Cantor would sing, see his audience applauding and hear nothing. For a joke, he’d see his audience laughing and hear nothing. It was confounding, I imagine.”

“The glass front,” says Shadoe Stevens, [4] “replaced a more conventional studio wall. Old radio shows originated in hermitically sealed studios. Carpeting and thick drapes cloaked the walls to manage the sound. A studio, large enough to seat a large audience, didn’t exist.

“When Cantor wanted to see the live audience, the natural response was to set up a glass wall,” says Stevens. “The audience can see and hear him; he could see the audience. If microphones picked up the audience clapping or laughing, a hollow, cavernous sound would go out over the air. Cantor had to deal with the silence.”

“The silence threw Cantor for a loop,” Mel Simons says. “He demanded NBC remove the glass partition, regardless of what the technicians said. NBC took away the partition and found a way to ensure a broadcast-quality show.

“Every radio comedian was indebted to Cantor. They all had the same problem. They needed to hear the audience response.

By 1928, NBC affiliates owned the best technology. The network earned $3 million dollars from the sale of time to advertisers. Affiliate stations paid NBC $45 an hour for Red and Gold Network shows; affiliates could sell local advertising on these shows. NBC paid affiliates $45 an hour to air unsponsored shows.

CBS focused on content and, by 1928, had more listeners than all the NBC networks combined. It also had more rewarding deals, with its affiliates, than did NBC. The best technology was great, but money spoke loudest.

Starting in August 1929, CBS paid affiliate stations from $125 to $1250 an hour for commercial shows. Unsponsored shows were a choice for affiliates. In 1929, CBS reported a profit of $475,000.

By 1933, CBS offered a wide-range of shows, including light entertainment, drama, talks and sports. NBC offered listeners a similar range of show, but placed more emphasis on classical music and religious shows than did CBS. It may be the case that NBC targeted rural listeners more than did CBS.

Technology caught up with demand, making it possible to air shows to all states, from a central location. In 1936, the NBC Orange Network stations became part of its Red Network; the Gold Network became part of its Blue Network. Two versions of most shows aired, on the same day: once for the east coast and Central Time zone, once for the west coast and Mountain Time zone.

The two networks, NBC and CBS, developed huge interest in radio among Americans. By the middle 1930s, sales of radio sets topped $425,000,000 a year. In 1938, there were 40 million working radio sets, mostly in living rooms across the USA; listening averaged three hours a day.

Radio advertising revenue grew from a few thousand dollars, in 1925, to $100 million in 1935. It was mostly natural growth, says Llewellyn White. “A hidden spring producing a brook that became a stream and then a torrent, making its own bed as it swept along.”

For Mel Simons, “network radio content didn’t get rolling until the late 1920s and early 1930s.” The first important event, in network radio, was moving ‘Amos and Andy’ to the Blue Network, in August 1929. This gave NBC a hugely popular national hit show.

“By 1932,” says Simons, “shows that defined network radio were on the air. Melodramas, such as ‘The Stolen Husband,’ which was the first soap opera, started in 1931. ‘Ma Perkins,’ which left the air in 1960, began in 1933, as did ‘The Romance of Helen Trent.’ ‘Our Gal Sunday’ began in 1937.

“By 1932,” says Simons, “shows that defined network radio were airing. Melodramas, such as ‘The Stolen Husband,’ which was the first soap opera, started in 1931. ‘Ma Perkins,’ which left the air in 1960, began in 1933, as did ‘The Romance of Helen Trent.’ ‘Our Gal Sunday’ began in 1937.”

Eddie Cantor and Ed Wynn came to radio, in 1931, with their vaudeville acts. Cantor was a saloon singer who became a Broadway star. He replaced Maurice Chevalier on “The Chase and Sanborn Hour.” Cantor sang, joked and performed brief skits. Chatting about his wife and their five daughters, Cantor formed an intimate bond with listeners.

Ed Wynn adapted his character, “The Perfect Fool,” for radio. Texaco sponsored his show; he became the “Texaco Fire Chief.” Supposedly, he claimed he spent almost a million dollars over 25 years promoting his “Perfect Fool” character, but in few weeks, the “Texaco Fire Chief" character erased "The Perfect Fool."

Until 1931, network radio aired mostly music and sitcoms, such as “Amos and Andy.” The success of Cantor and Wynn showed persona worked. Now, one person, with a supporting cast, carried the show. In May 1932, Jack Benny, the most enduring network radio persona, began a weekly show; in October, satirist Fred Allen also began a weekly show.

“By the middle 1930s,” says Simons, “the mainstay shows of network radio were on air.” About 95% of all homes, in the USA, owned at least one working radio, in 1935. The US Census reported the resident population at 127.25 million.

Marketers drooled. A network radio show, with a 30 rating, which was common, reached more than 40 million men, women and children. A commercial, heard across the USA, on radio, cost little more than did a full-page advertisement in the most read daily newspaper, in a large city, such as New York or Chicago.

A large daily newspaper might reach 750,000 readers. Radio commercials reached many times more men, women and children as did newspaper advertisements, for about the same cost. This gave radio had a huge edge.

“When I was a kid,” says Bobb Lynes, “the voices on radio, such as Rudy Vallee or 'Amos and Andy' were friends. I was born in 1935, when network radio began to hit its stride. I grew up during the late Depression and the Second World War.

“Characters, such as ‘Fiber McGee and Molly,’ came into our home, every week; into our living room. We, my parents and I, spent thirty minutes listening to ‘Amos and Andy,’ thirty-nine weeks a year. These shows built morale, did good work for the war and gave us hope for the future.

“In the 1940s, Tuesday night on NBC Radio was a must listen. It was the same as Thursday night, on NBC Television, in the 1980s, with “Cheers,” “Seinfeld” and other comedy shows. Tuesday night, all those years ago, NBC Radio aired ‘Amos and Andy,’ Red Skelton, ‘Fiber McGee and Molly’ and Bob Hope back to back, in a two-hour block. It was incredible.

“Except for Bob Hope, I guess, you might call the shows ‘Musketeer Radio.’ Network radio was for everyone, children, parents and grandparents. Today, many or most hit shows on television use gruesome plot lines. Rarely were network radio shows not for everyone.”

Hope, Eddie Cantor and Jack Benny, comedians with staff writers, avoided the censors. Fred Allen, writing mostly on his own, could not. Hope, Cantor and Benny, in order, focused on adolescents in adulthood roles, daughters and self-effacement; Allen satirized news headlines, with inbred controversy.

“Creation,” Allen wrote, “is imposing form on something that has no apparent form.” His weekly radio scripts gave form to empty sheets of paper. The satire he, with Herman Wouk and Arnie Auerbach, wrote sent the drones into action.

Once the script created, the little men, such as censors, deleted, edited and changed content. Allen couldn’t satirize Ford, as it might one day be a sponsor, or the network that aired his show. When Allen refused to excise innocent comments about NBC, a vice-present arranged for the show to go silent when a character read the offending lines.

Hope, Cantor and Benny, among other network radio comedians, offered vocal support for Allen. In a week or two, NBC relented. Allen said, “The executive is no longer with the network. I am. If this is justice it is news to [the executive].”

On television, now, most anything goes; especially topics and depictions. A current show, “The Tudors,” about Henry the Eighth, features nudity in most episodes. This show airs in prime time on the publicly owned Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

“There was a huge difference in the tone and content heard on network radio,” says Lynes, “than you see on network television, today. Network radio, at least on the surface, worked squeaky clean. Top quality writers helped comedians and drama shows work around the censors.

“Thanks to his shrewd writers, Bob Hope was popular as risqu� comedian, using many double entendres and knowing remarks. He might say, ‘I have much money invested in sweaters.’ His reference was to the fad for young girls to dress as the ‘Sweater Girls,’ popular as pin-ups during the war. His comment also evoked thoughts of why Lana Turner was a huge star.”

In “The Listless Murder Case,” Philo Vance, on the eponymous series, conducted an especially informal, intimate interrogation of a female suspect; this was Tuesday 3 March 1949. The suspect wonders if his approach works. Vance says, “Something usually turns up.” She replies, “At this point, it’s usually my toes.” Good writing got that one past the censors.

“The writers,” says Lynes, “were able to tell a brief, risqu� story in a way that made it all right. Their skill kept a G-rating for the shows. This was true for soap operas, mysteries and melodramas as well as comedy shows; it was essential for the success of a show.

“On radio, Bob Hope and other comedians never worked blue, but often near far edge of clean. If I was lucky, my parents let me stay up late to hear Hope. Sometimes, my mother would send me to bed half way through his show.”

“Our household stopped,” Mel Simons says, “when it was time for ‘Gang Busters,’ a long-airing crime-anthology show. My father loved this show. It was an early reality show; listeners heard true-life police stories, long before ‘Dragnet.’”

Network radio offered a show for anyone and every interest. As with network television, no one show defines network radio and there were many firsts, as expected. Among the many shows on network radio, three stand out: “Amos and Andy,” the “Jack Benny Program” and “Gunsmoke.”

Amos and Andy

Although widely criticized, “Amos and Andy” broke much new ground for network radio and television. The show aired for 34 years, in various formats, on NBC and CBS. Deeply ingrained in the life of Americans, Amos and Andy attracted a large audience no matter what they did.

When morphed into a glorified DJ show, it had a huge audience. The “Amos and Andy Music Hall” aired from 13 September 1954 to 25 November 1960. On this show, Amos and Andy played records, DJ style, and talked about or with musicians, singers and others.

The “Music Hall” aired weeknights, a 7 pm, as did the original show, in 1927. Sometimes, ‘Music Hall’ aired for half an hour, other times for forty-five minutes. Whatever amount of time CBS needed to fill, wherever on its schedule, audiences found Amos and Andy.

In “Amos and Andy,” Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll created the “situation comedy,” the sitcom. Some vaudeville acts specialized in sitcom-like characters and brief vignettes. “Amos and Andy” went far beyond snippets, with well-developed storylines stretching over weeks. With few exceptions, every successful sitcom, “M*A*S*H” or “Cheers,” “Frasier” or “Friends, relied on the imagineering of Gosden and Correll.

“Amos and Andy” took its cue from a daily newspaper comic strip, “The Gumps.” An executive, at WGN-AM, where the show began, wanted to mimic the comic strip, on radio. “Amos and Andy,” aired as a strip, that is, every day, for 15 minutes at 7 pm, Monday to Friday.

The formula created by Gosden and Correll lead to much success on radio or television. Sitcom topics and depictions changed, radically, since 1927. The format remains mostly intact.

Gosden and Correll (above) are Amos Jones and Andrew H. Brown. Amos is dependable and pure of heart, a hard-working family man. Andy is a woman chaser, a recklessly overconfident, naive dreamer, forgivable and likeable.

“Andy is full of sass, fizz and fireworks,” says Leroy Jones, a former literary agent and OTR fan. “Amos is dependable, loyal, helpful, considerate and kind. Regardless of ethnicity, everyone connected with Amos, Andy or both.”

Together, Amos and Andy emigrated from Atlanta to Chicago, about 1925, moving to New York City in 1929. Entrepreneurs, they started the Fresh Air Taxi Company. The company name came from the fact their only car had no no front windshield.

The format of the show revolves around main characters, with different attitudes. Amos works hard. Andy is lazy. Amos is a family man, after his 1935 marriage. Andy does all he can to stay single and accumulate many girlfriends. The implicit conflict, although usually mild, was resilient enough to hang riotous storylines on.

“Amos and Andy” is about everyday topics. Andy wants to avoid an old girlfriend. Amos needs someone to replace him, at work, while he takes a day off with his family. Andy needs money. Amos won’t lend him money.

Trying to solve his money problems, Andy falls for a scheme brewed by George “Kingfish” Stevens. The scheme fails, miserably. They barely escape the mess. Amos sighs in regret.

Amos and Andy are archetypes, obvious, in varying forms, on all sitcoms. Sam Maloney and Norm Peterson, on “Cheers,” are versions of Andy Brown. Colonel Potter and Walter “Radar” O’Reilly, on M*A*S*H, are versions of Amos Jones. Ralph Kramden, on “The Honeymooners,” is a patent copy of George “Kingfish Stevens, a likeable schemer portrayed by Gosden.

Minstrel-like in the earliest years, Gosden and Correll developed sophisticated characters. “Amos and Andy” stressed essential American values, such as friendship, love, family, tenacity and a better future, among others. By 1931, maybe earlier, much deeper and more intimate portrayals, of Amos and Andy, were obvious.

Americans agreed with Amos and Andy. Listeners heard, through them, the great excavation of humanity for profit as it took form. Listeners, working women and men, of any ethnicity, connected with and through Amos or Andy.

“Amos and Andy” may be the most successful sitcom, ever. First on the Blue Network, of NBC, then on its Red Networks, the show was an unexpected hit, of huge proportions. The success, of “Amos and Andy,” didn’t fall when it moved to CBS, in 1939. Its sponsors, overtime, included Rinso, Pepsodent toothpaste and Campbell Soup.

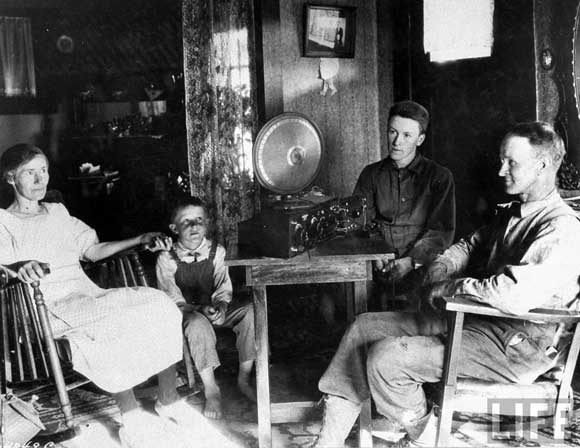

Correll and Gosden, in 1931,

swamped by mail and fans.

North America stopped, each weeknight, to listen to "Amos and Andy." At movie theatres, attendance fell drastically for the early evening showing, at 7 pm. To sell tickets, theatres aired “Amos and Andy” before the early showing, which moved to 7:30 pm; those who listened at home had time to walk to the neighbourhood movie theatre, afterwards.

During its second season on NBC, 1930, NBC estimated an average 40 million men, women and children listened to “Amos and Andy,” each weekday. That’s a 53.4 share, says Dunning, meaning that 53.4% of people using radio at 7 pm on weekdays listened to the show. Today, a television sitcom would have to reach 100 million or more viewers, for each episode, to match “Amos and Andy.”

The final episode of “M*A*S*H,” in 1983, and the 2010 “Super Bowl” equal the audience of “Amos and Andy.” Otherwise, the top sitcom, in 2010, “Two and a Half Men,” reached about 8 million viewers an episode. Top-rated episodes of “American Idol” reach about 16 million viewers.

In 1931, “Amos and Andy” used a storyline out of the newspapers, much as does “Law and Order,” today. Amos underwent a brutal police interrogation after the murder of a minor crook. The uproar was enormous. Chiefs of police, from all over the USA, spoke out, loudly, against the theme; few listeners seemingly complained.

Gosden and Correll decided to drop the brutal storyline. On Christmas Eve, 1931, Amos woke up from a horrible dream. “Dallas” used the same strategy to bring back its “Bobbie” character. “Newhart” ended its eight-season run on the same theme.

As a comedy, “Amos and Andy” is resilient. This, in part, is due to the continuous tweaking of its format and remaking of its central characters and storylines in newer sitcoms. Mostly, the resilience of “Amos and Andy” lives in the universality of its characters and their predicaments as well as top-notch writing.

Andy, for example, falls for beautician, Madame Queen. He asks to marry her, but changes his mind. She sues Andy for breach of promise. The storyline lasts for weeks, not an episode.

Ethnic concerns haunt “Amos and Andy.” Factual basis or not, if women and men believe something is true, they respond as if it’s true. Does the portrayal of Black characters, on “Amos and Andy,” lead Whites, for example, to harm Blacks, in any way?

The answer is no. Fair media research convincingly decides that such effects do not exist or exist in a limited way. Those predisposed to prejudice will embrace such views, in the face of contrary evidence.

Media reinforce existing ideas, especially mainstream ideas, such as family, gender and work. Viewers bring existing ideas to content. Content seldom changes ideas, especially in the short run; it reinforces more than it changes ideas.

The “Sopranos,” a hugely popular series on HBO, offered a sympathetic depiction of gangsters. After watching the show, no one suggested the police and courts go easy on gangsters because they’re good Americans. Entertainment diverts attention, but changes underlying attitudes, ideas and opinions little, if at all.

The portrayals, of Amos and Andy, are solid; each, in his own way, is compelling. If the characters were White, as if often the case, say “Radar” O’Reilly or Sam Malone, no questions arise. What is important is to portray Black characters, honestly, as good Americans, not, say, as whores or pimps, hopheads or drug dealers.

The criticism, that White actors portray Black characters, sometimes in blackface, is glib. It’s much the same as saying a gay actor can’t portray a non-gay character or the converse. Gosden and Correll portray Amos and Andy sympathetically, imbuing much dignity and respect. In retrospect, the occasional use of blackface is regrettable, but acceptable at the time.

Blackface acts, such as “Two Black Crowes” or Emmett Miller, didn’t find the widespread popularity of “Amos and Andy.” The fuller development of Amos and Andy, as characters, trumped the minstrel show, step-in-fetch-it, shallow portrayals of Blacks, common in the 1920s and 1930s. On “Amos and Andy,” listeners heard the humour, heard themselves, not the ethnicity.

“Amos and Andy” achieves the better end, in an enduring and endearing way. Amos is warm, reliable, tolerant and honest. Andy is harmless; chasing women knows no ethnic limits nor does liking to sleep late or a mild reluctance to steady work.

National advertisers, even today, are skittish; the slightest hint of controversy leads to cancelled contracts. If the criticism of “Amos and Andy” were valid, its A-list advertisers would not have amassed or stayed with the show. Rexall, for example, a family centric pharmacy chain, which sponsored only squeaky-clean shows, such as “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet,” also advertised on “Amos and Andy.”

If “Amos and Andy” lived off degrading Blacks, would the outcry about its police brutality storyline have been so massive among those with a stake in the issue? The answer is no. Those who railed against the storyline did so because they recognized the audience, for the show, would soon recognize themselves as Andy.

It was the huge audience, for “Amos and Andy,” that fired the ire of those who opposed the storyline. They knew such a large audience wasn’t the result of ethnocentrism. They knew they had to act fast to protect their stakes.

In the end, ethnicity is not an issue. If Amos and Andy were Irish, someone could voice the same concerns and none would care. The issue is about what’s at stake for those who complain.

Gosden and Correll claimed to make fun of human nature. Their claim is valid, as any "Amos and Andy" storyline is easily applied to any sitcom or character. "Two and a Half Men," the top television sitcom in 2011, clearly roots in the work of Gosden and Correll, as did "Cheers" or "Frasier."

Eddie Anderson, Dennis Day, Phil Harris, Mary Livingstone, Jack Benny, Don Wilson and Mel Blanc, about 1941.

Jack Benny on Radio

“Jack Benny had a secret,” says Mel Simons. “It was finding a way to become a media star on the wrong end of the joke.” In vaudeville, one partner delivered a straight line: “Why did the chicken cross the road?” The other partner delivered the punch line: “To get to the other side.”

The reward for delivering the punch line, evoking the laughter, is getting the most attention. As a result, in comedy duos, such as Abbott and Costello, Gallagher and Sheen or Martin and Lewis, he who delivers the punch line gives takes second billing. Jack Benny was different: he took the punch line and had top billing.

“Benny didn’t need to get the laugh,” says Simons. “Laughs, on his show, came at his expense. For example, on the Sunday 17 November 1946 show, Ronald Colman says, “When [Benny] curtsied, his toupee fell off,” and got a 19 second laugh. This is a long, long laugh.”

The name, Benny, was on the show. “He didn’t need the punch line,” says Laura Leff (above). [5] “If the audience laughed, it was because they were listening to the ‘Jack Benny Program.’ This was his philosophy.”

His deep, resilient self-confidence helped, too. “His awareness of his place on the show,” says Leff, “allowed Benny to take, not give, the punch lines. He was a player, as were other cast members, even though his name was on the show. Benny is almost alone among celebrities; few are willing to seem to be second banana.

“Frank Nelson, a regular player on the Benny show, told me a story about Eddie Cantor,” says Leff. “If, during rehearsal, anyone got a big laugh, the writers rewrote the line for Cantor to give, on the live show. I’m not knocking Cantor. This was and is common practice.

“Benny didn’t need as much attention. Spreading the punch lines around provided balance. All the players felt more a part of the show.

Dick Lane, who portrayed the publicity agent for Jack Benny, told Leff about seeing a “Red Skelton Show.” “Lane said that after a few minutes, maybe five minutes, Skelton dropped the script on the stage and started adlibbing. This kept him in control and his players off balance.

“On Benny, everyone was a comedian,” says Leff. “Maybe not Don Wilson, the announcer, who voiced the commercials, but everyone else, for sure. Spreading the punch lines around and being the victim of most of those lines was all right for Benny and good for his show.

“One Benny show involved a bus tour. Benny only appears in the last five minutes. This led to a call, right after the show finished, from William Paley, who ran and mostly owned CBS, at the time.

“Paley says, ‘Jack, you have [guts] for appearing so little on your show. It was a debut show, too.’

“Benny said, ‘It was a good show. It got many laughs. Tomorrow, people will be saying wasn’t the ‘Jack Benny Program’ funny last night.’

“No matter who gave the punch line, Benny was credited for the laugh. It was his show. Most comedians find it difficult to allow others to evoke the laughter. Benny, a comedic actor, found it easy.”

Jack Benny came to network radio on Tuesday 29 March 1932, appearing on the “Ed Sullivan Show.” Sullivan was the Broadway columnist for the New York “Daily News.” His show had a large audience on the CBS Radio network. The exposure was good for Benny, who wanted to move away from vaudeville and Broadway.

“At least part of the Benny monologue, on Sullivan, was written by Al Boasberg,” says Laura Leff. “The first line, by Benny, was, "This is Jack Benny talking. There will now be a slight pause while everyone says, 'Who cares?'"

Corny yet effective, it got Benny his own show. “Douglas Coulter, of J. W. Ayer, the advertising agency, heard Benny on Sullivan. He signed Benny to emcee the ‘Canada Dry Ginger Ale Program.’ On the advice of George Burns, a great friend of Benny, Harry Conn joined Boasberg to write the Canada Dry show.

“Sadye Marks, wife of Jack Benny, joined the show in July as Mary Livingstone,” says Leff. The Livingstone character is novel for 1934. Unmarried, she works on the Benny show and lives on her own."

Benny ostensibly rescued Livingstone (above, with Benny) from a dead-end job at the May Company, a department store chain. Livingstone isn’t dependent on a man or doltish. She’s a strong, intelligent, self-reliant woman.

Don Wilson joined the show in 1934 and Frank Nelson made the first of his great many appearances. Singer Kenny Baker joined in 1935. The show moved from New York City to Los Angeles in June 1936.

“For the 1936 season,” says Leff, “actor and musician, Phil Harris joined Benny as his ostensible bandleader. Andy Devine also joined the cast. Mel Blanc appearned as an Paramount Studio executive; in 1939, he regularly portrayed Carmichael, the Polar Bear that guarded the vault below the Benny house.

“On the advice of Fred Allen, Ed Beloin and Bill Morrow became head writers on the show. Sam Perrin also wrote for the show.” So, too, did Howard Snyder and Hugh Wedlock, as needed.

Benny and Allen during the fued years.

“During the 1936 season,” says Leff, “the feud with Fred Allen started; it lasted, off and on, for twenty years. An unscripted part of the Allen show, ‘Town Hall Tonight,’ featured a 10-year old violinist, Stuart Canin, who played, masterfully, ‘The Bee,’ by Shubert. After the performance, Allen said, ‘A little fellow, in the fifth grade at school and already he plays better than does Jack Benny.’

“Allen made this comment on the east coast version of his show. In 1936, broadcast-quality recording technology didn’t exist. All network radio shows were done twice, once for the east coast and, later, for the west coast.

“For this reason, no one knows exactly what Allen said on the west coast version that Benny heard; no recording exists. Benny claimed Allen said, after Canin performed, 'Jack Benny should be ashamed of himself.'" Later, Allen claimed he said, "Jack Benny should hide his head in shame. The horsehairs, in his bowstring, want to crawl back under the tail of the horse. The cat-gut, of his violin string, wants back into the cat."

“At the end of that show, Benny says, ‘Mary, take a letter to Fred Allen. Tell him I’m not ashamed of my playing. I could play ‘The Bee.’’

“Benny aired at 7 pm on the east coast, Allen on Wednesday at 9 pm. Allen thus had three days to respond. Each week, he came up with something to egg on Benny.

In 1954, Allen wrote, “I didn’t plan anything. I didn’t want to explain [the feud] would be good for us. With our smaller audience, it would take an academy award display of intestinal fortitude to ask [Benny] to participate …. I would be hitching my gaggin’ to a star. All I could do was hope [Benny] would have some fun with the idea and that it could be developed.”

“Allen and Benny went back and forth for a few weeks. In March 1937, Benny took his show to New York City. Allen and Benny had it out, appearing on each other’s show. Thereafter, the feud faded in and out until Fred Allen passed away, suddenly, in 1956.

After a surprisingly popular one-time guest appearance, Eddie Anderson joined Benny as his valet, Rochester van Jones. That was 1937. There were few Black characters on network radio and none in central roles, such as Rochester.

For the 1939 season, multitalented Dennis McNulty, as Dennis Day, replaced Kenny Baker. “To end a break in the auditing of Day,” says Leff, “Benny said, ‘Oh, Dennis.’ Day replied, ‘Yes please.’ This broke up the cast and crew, getting Day the job.”

“Dennis Day,” says Mel Simons, “allowed Benny to take comedy to a higher plain. His relentless attempts to bully or make a fool of Day always backfired. Often, the ostensibly dim-witted Dennis Day character out-smarted Benny.”

Mary Livingstone punctured Benny more than did any other character on the show. Don Wilson took jokes and jabs about his weight so well, it made Benny seem a bully. The self-assured vanity of Phil Harris lacked the black streak that sometimes snuck into the Benny character.

Harris portrayed the bandleader on the “Jack Benny Program.” Many listeners believed he was the bandleader. Although Harris had a band that toured and played Hollywood clubs, he was an actor on the Benny show. “Mahlon Merrick,” Laura Leff says, “was the musical director for Jack Benny, from the late 1930s through the early 1950s. As with many of the writers, Merrick did not leave the show, never to return.”

In 1939, with cast and writers in place, the “Jack Benny Program” was ready to soar through the 1940s and into 1950s. Beloin and Morrow refined the Benny character. The punch line targets received high polish. Benny was a greedy miser, he bought one gallon of gas at time. He was vain, believing himself a great violinist and calling himself, Jascha Benny to confuse himself with virtuoso, Jascha Heifetz. He starred in bad movies, which weren’t as bad as the cast claimed. His age was forever 36 or 39 years old. His woman chasing was most always ill fated.

For the 1943 season, Benny hired a new writing team. They were George Balzer, Sam Perrin, Milt Josefsberg and John Tackaberry. The new team remained until the final “Jack Benny Program.”

“When we got off air on Sunday night,” Balzer told Leff, “we never knew what we were going to do for the next [show]. Somehow, by Tuesday, we had an idea for the next show. Well, Tuesday, 20 November 1945, came and we hadn’t thought of anything.

“Wednesday morning we, Perrin, Josefsberg, Tackaberry and I, went to [Benny’s] house. We said, Nothing is happening.’ Maybe, if we all sit here together, for a while, something will come up.’

By noon, Wednesday, we still had no show. [Perrin] said to [Benny], ‘Why don’t we have a contest where we ask our listeners to write lyrics for a song. Merrick can put a melody to them. Then, we’ll have a contest.’

“Jack says, ‘No, I don’t want to go through that.’ We’re thinking a little bit more and I said, ‘Jack, I have an idea. You know, we hear so much on the radio, [such as] I like so-n-so toothpaste in twenty-five words or less to win a prize. You like so-n-so potato chips in twenty-five words or less.

“Why don’t we ask people to write in and say, “I can’t stand Jack Benny because, in twenty-five words or less. We give the best one a prize.’ There’s absolute silence in the room.

“The other three writers look at me. Benny looks at me. I don’t know what to do.

“[Benny] gets up out of his chair and walks across the room. He puts his hand on my shoulder. He says, ‘That’s it. That’s what we’re going to do.’

“We said, ‘Jack, you can’t.’ He said, ‘It’s what we’re going to do and not in twenty-five words or less. We’re going to give 50 words or less.’

“We did it. We were looking for one show. We ran that idea for eleven weeks.”

“I Can’t Stand Jack Benny” played on Benny as victim. Each of his character traits stroked over three months. The ratings spiked.

Judges for the contest were comedian and writer, Goodman Ace, actor Peter Lorre and Fred Allen. On joining the judging panel, Allen said, “I’m the greatest living authority on Jack Benny. I have seen him reach for his pocketbook.”

The contest received 277,000 entries. It took four weeks to decide on a winner. The ratings skyrocketed.

Carroll P. Craig, of Pacific Palisades, California, won the “I Can’t Stand Jack Benny” contest. Second prize went to Charles S. Doherty, of Cleveland, Ohio. Joyce O’Hara, of Detroit, Michigan, won third prize.

Ronald Coleman and his wife, Benita, were now regular guests on the Benny show. Coleman read the winning entry, in the “I Can’t Stand Jack Benny” contest, on 3 February 1946. “I can’t stand Jack Benny because ‘he fills the air with boasts and brags, and obsolete, obnoxious gags. The way he plays the violin is music’s most obnoxious sin. His cowardice alone, indeed, matched by his obnoxious greed. And all the things that he portrays show up in my own obnoxious ways.”

Craig captured Benny, well. As Coleman said, after reading the winning entry, “The things we find fault with in others are the same things we tolerate in ourselves.” The character, Jack Benny, was all men and women.

The “Jack Benny Program,” on network radio, ended without fanfare on 22 May 1955. “It was the last show of the season,” says Bobb Lynes. “I’m not sure I or anyone realized it was last show, ever.”

Benny, wrote Robert Taylor, developed the possibilities of the sitcom. He created a vain, miserly and self-important character loved by millions of listeners. “Benny seemed inseparable from [his] character … his comic inspiration, the expressivity of the pause, [closer to] poetry than prose.

Gunsmoke

“‘Gunsmoke’ is my favourite OTR drama,” says Ken Meyer, who hosted “Radio Classics” on WEEI-AM, in Boston. "The writing is extra-ordinary and adult themed. The actors formed a stock company. Listeners heard mostly the same actors, each week, credibly portraying different characters.

“One week John Dehner, for example, would be a colonel in the army and the next week he might be a ninety-year-old man. Each role he played on ‘Gunsmoke,’ he did well. Part of the thrill of listening to the show was hearing Dehner."

The premise for “Gunsmoke” was simple. Matt Dillon, as a marshal, protects those who live in a dangerous town in the American west. The goal was to create a western drama that appealed to adults.

The show developed over two or more years, says Dunning. Norman MacDonnell and John Meston directed and wrote radio network shows at CBS. William Paley, head of CBS, had long wanted a Phillip Marlowe character set in the old west.

About 1950, MacDonnell and Meston began talking about an adult-targeted show, with a western theme. The adult theme meant character depth was important. To this time, westerns, on network radio, featured limited character development, such as “The Lone Ranger.”

“Pagosa,” an episode in the CBS radio series, “Romance,” introduced a reluctant marshal in a dangerous town in the American west, around 1870. William Conrad portrayed the marshal, “Pagosa.” This wasn’t an official pilot for “Gunsmoke,” rather, as the Old-time Radio Researchers Group reports, a stepping-stone to the show.

“Until 1952,” says Mel Simons, “westerns were targeted to children. The most successful westerns, ‘Hopalong Cassidy,’ ‘The Lone Ranger’ and ‘Roy Rogers,’ were more comic books of the air than serious drama.

“’Gunsmoke’ changed the western drama on radio and later on television. Matt Dillon was a US Marshal in Dodge City, Kansas. His girlfriend, Kitty Russell, was a saloon-girl, portrayed by Georgia Ellis. Parley Baer portrayed Chester Proudfoot, the unofficial deputy marshal, who carried Civil War injury, both physical and psychological.”

“Each character, on ‘Gunsmoke,’ had emotional depth,” says Ken Meyer. “Although not openly used, every character had a back-story. Doc Adams, for example, hid deep emotional scars that led him down into alcoholism. Over time, listeners developed their own ideas about character motivation and predictability.”

The characters, plot and themes, each remaining in a shade of grey, not black-and-white, were new to network drama. A saloon-girl as the lead female character was daring; she surely had links to crime and prostitution. The honesty of Chester, a central character, was questionable; his Civil War experience seemingly left him morally as well as physically damaged.

Doc Admas, Matt Dillion,

Kitty Russell and Chester Wesley Proudfoot

“Matt Dillon was strong and silent, reluctant and determined, sad and often somber,” says Ken Meyer. He was unlike more outgoing cowboy stars, such as Roy Rogers. Dillon, as Paley hoped, resembled Phillip Marlowe, the dysphoric private detective created by Raymond Chandler, more than he did “Hopalong Cassidy” or “The Lone Ranger.”

“Dillon often didn’t save the day,” says Meyer. “He seemed to act more out of duty than calling. He seemed prone to bouts of deep regret and reluctance and was much crustier than the television version.”

Doc Adams, Dr. Charles Adams, which Dunning describes as ghoulish, is another novel network-drama character. In the first episode, of “Gunsmoke,” his blood lust overwhelms Dillon. At first, Doc, on “Gunsmoke,” was similar to the Doc Cochran character on “Deadwood,” the HBO series: a mercenary, shameless alcoholic, with a checkered past that included deep disappointment and scarring.

Howard McNear portrayed Doc Adams on radio. On television, McNear portrayed Floyd Lawson, the chatty, easygoing and nerdy barber on the “Andy Griffith Show.” The distance between these characters, in which he was equally convincing, confirms the ability, of McNear, as an actor.

Parley Baer portrayed Chester, the maybe shifty, maybe deputy sheriff of Dodge. “Baer was an excellent actor,” says Ken Meyer. “For the first few episodes, of ‘Gunsmoke,’ Chester had only a first name. During a rehearsal, Baer, adlibbing, blurted out the full name, Chester Wesley Proudfoot, which stuck.

“Baer was ubiquitous on radio. On the first season, of “Dragnet,” he played a most hideous, obese criminal, with the creepiest laugh. The episode, called ‘The Big Bomb,’ was scary. Talking about that character scares me.

“Baer was memorable. He may have reprised the hideous character, from “Dragnet,” or one like it on ‘The Adventures of Phillip Marlow. I interviewed Baer several times. We became friends.”

Howard McNear, William Conrad,

Georgia Ellis and Parley Baer

“Gunsmoke,” Meyer says, “is unique for its sound effects. It likely featured the best sound-effect work in radio, ever. Every time I listen to the show, these days, I hear another level of sound effect that makes listening exciting.”

Dunning, too, offers special comment about the sound effects on “Gunsmoke.” He says, “When Marshal Dillon went out on the plains, you didn’t need a narrator to know what was happening. When a jail cell door [unlocked,] you heard every key on the ring drop.” When Dillon walked on the boarded sidewalks of Dodge, you heard the hollowness and the clink of his spurs, which missed enough to make it sound true.

The booming voice, of William Conrad, made “Gunsmoke” a radio hit. “He conveyed, with his voice,” says Meyer, “the idea he was six feet, seven inches tall and a western version of “Superman.” He was not. Conrad was short, maybe five-foot six inches tall, and somewhat overweight.

William Conrad as Matt Dillon

The vocal image of Matt Dillon resonated with executives at CBS Television. Developing “Gunsmoke” for television, they faced the image Conrad created, vocally, and left in the imagination of the listener, with Conrad, the man. “He didn’t fit the image he created,” Mel Simons says.

In 1955, “Gunsmoke” was moving from radio to television, without Conrad. The producers wanted the image Conrad projected, a tall and lean, intelligent and thoughtful marshal of Dodge. James Arness (below) got the role of Matt Dillon, on television.

Left and Right, James Arness as Matt Dillon;

centre with Johnny Carson.

“Conrad had a token audition for the television role,” Simon says. Arness fit the vocal image created by Conrad. Embittered, Conrad portrayed Dillon on radio until 11 June 1961, when CBS cancelled the show. “Gunsmoke” aired on CBS Television until 31 March 1975.

“The irony,” Mel Simons says, “is Conrad had three hit television series, two on CBS, based on his girth. From 1971 to 1976, he portrayed ‘Cannon,’ a portly private eye who engaged in more car chases and good meals than fistfights. Conrad portrayed district attorney Jason Lochinvar, on ‘Jake and the Fatman,” from 1987 to 1992. He was less successful as the eponymous lead on ‘Nero Wolfe,’ a 1981 series that NBC aired for thirteen weeks.”

Gerald Nachman thinks “Gunsmoke” bridged the comic-book quality of much early radio and the gritty realism of movies, plays and some television, in the early 1950s. At first, any idea the Beat Generation affected “Gunsmoke” seems farcical. Listening, again, to William Conrad portraying Matt Dillon, on radio, the inference seems less distant.

The rhythm of the Beats arguably exists. So, too, does their relentless sense of loss and duty. Dillon may embody the collective identity of the Beats; that is, someone who had love that’s now gone, never to return.

The End

In 1945, says Norman Finkelstein, there were more radios than bathtubs in American homes. “Radio,” Mel Simons says, “helped Americans survive the disorder of the 1930s and first half of the 1940s.” Bobb Lynes says, “Radio performers were our friends, in those dark days. We welcomed them into our homes.”

“By the middle 1950s,” says Simons, “the era of OTR was over. Most of the hit shows moved to television or left the air. Some shows, such as ‘Our Miss Brooks’ and ‘Gunsmoke,’ aired on radio and television, at the same time.

‘The Stan Freberg Show’ was the last new network radio show. It aired, on CBS, from 14 July to 20 October 1957. The Freberg shows lives on, though, in a set of cult-classic CDs.”

“I was hypnotized by television, at first,” says Lynes. “I turned my back on radio. Then, suddenly, the radio I knew was gone.”

The final day of network radio was Sunday 30 September 1962. The last show, “Suspense,” aired at 6:35 pm. “Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar” aired earlier in the day. “Suspense” ran for twenty-two years and “Dollar” for fourteen years, both on CBS. At 7 pm, the era of network radio was over and done.

It seems possible to narrow the OTR window even more. “My favourite shows,” says Simons, “aired in the late 1930s until to middle 1940s. Honestly, the corniness, of the earliest shows, gets to me.”

On the first “Jack Benny Program,” Monday 2 May 1932, the announcer, Ed Thorgerson, introduces Benny as “a suave comedian, dry humourist and emcee.” Benny says it’s his first professional appearance, on radio, which means he gets a pay cheque. This makes his creditors happy.

Hardly suave, this corny line might get a polite chuckle, today. Benny continues. His job is to introduce events that will happen whether he says anything or not. Writers Harry Conn and Al Boasberg struggled.

On Sunday 25 April 1948, Mary Livingstone, a character on the “Jack Benny Program,” says to Benny, “Oh, shut up,” after he tries to enter a conversation. Benny looks out to the studio audience. The subtlety of his look led to 23 seconds of laughter, says Laura Leff. This is a long, long, long laugh and light years away from his first show.

“OTR shows that aired before, say, 1936,” says Simons, are absurdly corny. Yes, writers and performers were working hard to discover how to use radio. Yes, they were making up the rules as they went along. Yes, corniness easily evokes emotion, in drama or comedy, but it makes the content stale, quickly.”

Many agree with Simons about the earlier OTR. “I find the “Jack Benny Program,” from the late 1930s, more spontaneous,” says Laura Leff. “The cast is loose. There are surprises. There are mistakes. Shows from the late 1930s are more an adventure than, say, episodes in the late 1940s, although the show remained hugely successful.

“The later Benny shows,” says Leff, “are more formulaic. Characters moved through the show as if in a revolving door. A little of the magic is gone by the late 1940s and certainly by 1952, when Phil Harris left the show.

“Phil Harris got his own show, with wife, Alice Faye, starting in the fall of 1946. His show aired immediately after the ‘Jack Benny Program,’ at 7:30 pm. Harris had to leave the Benny show, by 7:15 pm, so he could warm up the audience for his show. The writers worked around this fact, well, but a formula began to take over about this time.”

“After the War,” says Bobb Lynes, “more shows were transcribed, that is, pre-recorded. Bing Crosby, the top singer, of the time, invested heavily in recording technology. He preferred to tour or travel and the new technology let him record shows a month in advance, if he wanted.”

“My personal favourite shows,” says Mel Simons, “are from the 1940s and 1950s. This is when talent, technology and profits from advertising benefited network radio content the most. The quality peaked about this time.”

Increasingly, performers, writers and directors created polished, urbane and often subtle programming; the ‘Oh, shut up’ laugh, on the ‘Jack Benny Program,’ is an example. The state of technology, before the USA entered the War, in December 1942, carried radio through the war. “The product was superb,” says Simons.

“OTR had a good, long run,” says Simons. “We’re fortunate many of the old shows were saved. It was a memorable time, a golden age for radio, some say.”

Many shows didn’t survive the trash bin. “Only five complete ‘Fat Man’ shows remain,” says Dr. Charles Laughlin. “Those recordings were saved by someone willing to wade, knee deep through garbage.”

Himan Brown tried reviving network radio. On 6 January 1974, the “CBS Mystery Theatre” premiered. Brown committed to seven shows a week: one show, from scratch, every two days.

CBS gave Himan airtime, moral support and little else. Many CBS Radio affiliates didn’t air “Mystery Theatre.” Some affiliates plugged into schedules without predictability.

Brown had to scramble to find production money. Writers earned $300 for a 48-minute script. Actors and crew worked for scale or for no fee. Other ways, “Mystery Theatre” succeeded: it aired until 31 December 1982 and won many awards.

In 1929, network radio offered advertisers a huge advantage for a relatively low cost. In 1982, “Mystery Theatre,” was too little, too late, for that form of radio.

The era of network radio closed on a whimper. By 1962, radio, as a local medium, was hugely profitable. The economics of radio shifted. Network shows were far too expensive to produce, given possible revenue. In comparison, DJs playing records mixed with a little local news cost a pittance and returned huge profits.

Radio gave Americans access to a much wider world and lifestyle than did print media. In 1929, Lynd and Lynd report, “The rest of the world is still [far away], but [radio is] doing much to break down this isolation. I have 120 stations on my radio, said a [factory] worker. Meanwhile, the president of the Radio Corporation of American [RCA] proclaims an era is [near] when ‘the oldest and newest civilizations will throb together at the same intellectual appeal and to the same artistic emotions.’”

The head of RCA overlooked societal and cultural brakes on the common throbbing of nations. Movies, music and television would impose an American throb on the rest of the world. At home, network radio solidified America, levelling awareness, eroding understanding and rewarding inertia.

The audience for network radio was about twice that of newspaper readership: 80 million and 46 million, respectively. Newspapers localized news. Radio nationalized content, thus levelling it.

Listeners in Peoria, Illinois, had to understand as well as those in New York City or Los Angeles. Societal references simplified. The lowest common denominator became the target.

Suddenly, too, it was all right to spend three hours a day diverted from the larger issues of life by “Amos and Andy,” “The Romance of Helen Trent” or “Suspense.” The novelty did not wear off this shock to participatory democracy. Today, video games divert attention from larger issues, but it began with radio.

Radio, for America, was a huge shift. Europe built on wide base including music, art and conversation as well as print. America, built on print, that is, books and newspapers.

The American idea was that solo use, readying, led to well-founded personal opinions. Self-reliance, in thought and action, was the message of the founders. Radio wrecked this ideal.

Each week, radio handed 80 million men, women and children, across the USA, the same content, at the same time. Geographic distinctions wobbled. It was as if all Americans shared time and space, listening to the same stump speech or vaudeville act. A new form of participation took over; its vicarious nature mislead.

Newspapers hoped to bedrock thoughtful personal opinions. Radio took much pride in supplying meaning with content. As Lazarsfeld and Merton said, if it’s important, it’s on radio; if it’s on radio, it’s important.

Radio awarded authority in a new way, too. Awareness replaced reflection. The candidate or product that got the most attention, on radio, won the election or made the most sales.

Before radio, diversion or entertainment lived in the public realm: bars, theatres, fairs or buskers; newspapers provided a little diversion, comics or a humorous report. Radio delivered diversion into living rooms, on demand and mostly free. Once paid off, the cost of radio was suffering through advertisements and then, only maybe. Many listeners told researchers how much they enjoyed the commercials.

Radio entertainment approved of compliance and reinforced conventional acts. Storylines, which often portrayed women as dependant, doltish or unrealistic, urged them to marry, have children and not to enter the workforce unless widowed; there were few exceptions. This emphasis further confirmed the authority of the conventional, urging conformity and enabling exploitation.

Apathy and inertia increased as radio use grew; this didn’t seem the case with literacy and newspapers. Contact with family and friends decreased, replaced by vicarious contact through radio: “Did you hear ‘Inner Sanctum’ last night?” As Lazarsfeld and Merton said, radio narcotized rather than energized.

The same criticism applies to television, ten times as much. Billie Holiday, the singer, supposedly said she knew she kicked heroin when she could no longer watch television. Such concerns first appeared about network radio and then applied to television, video games and the new breed of cell phones.

Still, radio, network or local, uniquely fulfils needs. Radio evokes imagination much the way print supposedly urged rational and independent thinking. Neurochemical rewards flow from flexing the imagination.

Each listener to network radio enjoyed his or her personal image of the vault below the home of Jack Benny, guarded by a polar bear named Carmichael. The bags beneath the eyes of Fred Allen provoked diverse images. “As my left eye said to my right eye, ‘Grab your bag and let’s go see what’s happening in Allen’s Alley.’” The pompous Senator Claghorn, who lived in the “Alley,” evoked images based on political and geography or prejudice.

The richness of the images was private. On radio, Stan Freberg could fill Lake Michigan with Jell-O™, cover it with whipped cream and have the Royal Canadian Air Force fly over to drop a huge cherry on the top. “You can’t do that on television,” says Freberg, “because television only stretches the imagination to twenty-inches”; in 2010, that’s fifty-two inches, with the same non-effect.

Television doesn’t evoke imagination, only links among existing images. Radio is a hot medium for Dr. Marshall McLuhan: listeners must work up a metaphoric sweat creating pictures in their heads. Television is cool, presenting images that sweep over the viewer, as does a light breeze.

Local radio now withers, suffocated by relentless owners bent on exploiting every penny from stations. What we call Old-time Radio (OTR) endures. OTR thrives, in fact, its import aesthetic, not monetary.

OTR draws listeners for many reasons. There are those who seek it to relive comforting moments from their youth, all those years ago. Baby boomers, many barely able to recall network radio, want to find out more about their parents, who have left, and thus themselves.

For these reasons, among others, OTR fuels redemption myths. A redemption myth recasts the past in a more favourable light. Its goal is to stop that which goes bump in the night.

There’s also a much younger audience for OTR. They know nothing of redemptions myths. These listeners share an interest in all forms of drama.

Women and men enthralled by stories and storytelling form the main audience for OTR, as Ken Meyer said. From stories, told well, we learn about life and living: our way of living and other ways, too. Rummage through the remainder-bin, in any book or CD store, to know the fate of less well-told stories.

A well-told story, such as on “Dragnet” or a random episode of the “Lux Radio Theatre,” holds our interest. Stories told well are worth rehearing. The melodramas, which focused on timeless concerns, such as family, friends and danger, are thematically as relevant today as in 1940. The acting holds up, well, too. The unique opportunity to flex the imagination is a welcome benefit of OTR.

The voices, of the actors, stick. Voice is the largest part of the aesthetic of radio drama. Cadence, shading and even the silence ignite imaginations. Characters, as written, suggest images for voices to put across.

You can’t get this part of the aesthetic wrong. Your images are always right. When you hear the vocal images, you imagine, you picture what you’re hearing. You enjoy your private image, thoroughly, as a private dance, because it’s your own and the right one for you.

“The Fat Man,” says Dr. Charles Laughlin, succeeded on the unique voice, the vocal cello, of J. Scott Smart.” He was able to suggest the tricks and trials of a large person in a world of average-sized men and women. The portrayal was honest, not mocking or jocular, as is often the case.

There was the frustration, of “The Fat Man,” navigating a crowd. The joy he found buying two bags of peanuts, not only one. His thrill, when he met a woman oblivious to his bulk.

Vocally, William Conrad created an image of Matt Dillon, on “Gunsmoke,” as a huge, powerful and brooding man. Although listeners surely had private images of Dillon, they agreed Dillon was tall and broad-shouldered, with a furrowed brow. Conrad, short and portly, deeply resented that CBS didn’t cast him as Matt Dillon on television; he was the victim of his vocal skill.

Voices provoke images, as did Conrad and Smart. Scripts provide direction. Stories live in the sound, voice and effects, suggested by the script.

Storytelling, of any form, is an art. Art comes from grouping ideas, in a focused and shareable way, to make a point. Heroes, for example, are outsiders, with special skills. Matt Dillon is a model American hero. He’s a gunfighter in a dangerous town. He protects town folk and keeps order. Yet, the town folk never accepted him, fully: his murderous skill, as easily used against as for town folk, is a hint of unpredictability. He remains an outsider, where town folk are safe from him. His time spent with a saloon-girl, sketchy deputy and deviant physician.

“Radio,” wrote Fred Allen, the satirist, made it “possible for each [listener] to enjoy the same program according to [his or her] intellectual level and [his or her] mental capacity.” His meaning is true. “Amos and Andy,” “The Jack Benny Program” and “Gunsmoke” were accessible, simultaneously, on many levels.

“With the high cost of living,” wrote Allen, “and the many problems facing [him or her] in the modern world, all the [typical person has] left was [his or her] imagination.” Whereas radio poked and prodded the imagination, television took it away. The cool, moving image emphasis of television encourages the audience to amuse itself to death.

Radio once did better what television, today, does passably. The artistic achievements, of radio, despite societal concerns, remain singular, if, sadly, known only to a few. Only tape machines rewind and there are fewer of those every day; the future is a brave new world, where trivia between commercials equates with substance.

Notes

[1] Mel Simons is an entertainer and author specializing in live shows about OTR, especially trivia. He began overseeintrivia contests on “The Larry Glick Show,” on WBZ-AM, in the 1970s. He continues to appear regularly on WBZ-AM. Click here for a complete list of books by Mel Simons and information about how to purchase his books.

[2] Dr. Charles Laughlin is Professor Emeritus at Carleton University, in Ottawa, Ontario.

[3] Bobb Lynes is co-host, with Barbara Watkins, of “Don’t Touch that Dial,” on KPFK-FM, in Los Angeles, California. The show, now in it's 38th year, is all about Old-time Radio. Lynes served several terms as President of SPERDVAC, which aims to preserve and encourage radio drama, variety and comedy. Lynes co-authored, with Frank Bresee, “Radio’s Golden Years.”

[4] Currently, Shadoe Stevens is the announcer on “The Late, Late Show, with Craig Ferguson.” Stevens has one of the most widely recognized voices in the world. As programme director at KROQ-FM, in Los Angeles, he pioneered the Album Oriented Radio (AOR) format. He was the announcer on “Hollywood Squares” and, for several seasons, a “Square.” Stevens was a regular on the NBC sitcom, “Dave’s World.” He also authors a series of books for children, “The Big Galoot.”

[5] Laura Leff is Founder and President of the International Jack Benny Fan Club (IJBFC). Click here to visit the official IJBFC web site.

Sources

Fred Allen (1954), "Treadmill to Oblivion," published by Little, Brown.

Eric Barnouw (1966), “A Tower in Babel: a history of broadcasting in the United States to 1933,” published by Oxford.

Thomas DeLong (1991), "Quiz Craze: America's infaturation with game shows," published by Praeger.

John Dunning (1998), “On the Air: the encyclopedia of old-time radio,” published by Oxford.

John Dunning (1976), “Tune in Yesterday: the ultimate encyclopedia of old-time radio: 1925-1976,” published by Prentice Hall.

Gile Fates (1978), "What's My Line," published by Prentice Hall.

Norman H. Finkelstein (2000 [1993]), “Sounds in the Air: the golden age of radio,” published by Authors Guild Backinprint.com.

Walter Kerr (1975), “The Silent Clowns,” published by Knopf.

Charles Laughlin (1994), "J. Scott Smart aka the Fat Man." Three Faces East Press

Robert S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd (1957 [1929]), Middletown: a study in modern American culture,” published by Harcourt Brace.

Leonard Maltin (1997), "The Great American Broadcast," published by Dutton.

Marshall McLuhan (1965), “The Medium is the Message,” published by Anchor.

Elizabeth McLeod (2005), “The Original Amos ’n’ Andy: Freeman Gosden, Charles Correll and the 1928–1943 Radio Serial” published by McFarland.

Gerald Nachman (1998), “Raised on Radio,” published by University of California Press.

Walter Lippmann (1922), “Public Opinion,” published by the Free Press.

Geoffrey Perrett (1982), “America in the Twenties,” published by Simon and Shuster.

dr george pollard (2010), "Muck Made Meyer: interview with Ken Meyer," posted on grubstreet.ca

Tong Schwartz (1973), “The Responsive Chord,” published by Doubleday Anchor.

Irving Settle (1967), "A Pictoral History of Radio," published by Castle Books.

Anthony Slide (1982), "Great Radio Personalities," published by Vestral Press.

Warren Sloat (1979), “1929: American before the Crash,” published by MacMillan.

Robert Taylor (1989), "Fred Allen: his life and wit," published by Little, Brown.

Llewellyn White, (1959), “The Growth of American Radio: ragtime to riches,” in Wilbur Schramm, editor, “Mass Communications” published by the University of Illinois Press: second edition.

Disclaimer

This posting contains historical materials, analysis of these materials and conclusions drawn from the materials and analysis. As such, this posting may contain comments or depictions that some view as ethnocentric. The historical materials reasonably and honestly reflect the common use of images and language, opinions and attitudes extant at the time and place of creation.

dr george pollard is a Sociometrician and Social Psychologist at Carleton University, in Ottawa, where he currently conducts research and seminars on "Media and Truth," Social Psychology of Pop Culture and Entertainment as well as umbrella repair.

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Moose Knuckles

- Heavy on the Fluff

- Parking Meter Number 2

- Sjef Frenken

- The Diefenbunker

- How Do You Say

- Verbal Widdershins

- Jennifer Flaten

- Even Crazier After Vacation

- Kindle Me

- Oktoberfest

- M Alan Roberts

- Ode to Officer Cole

- Lies and Fear

- Checkmate

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- My 2016 in Review

- Summer Holiday

- Cat Man Cometh

- Streeter Click

- Tanna Frederick

- Support Us

- Shane McGown Live, Bio

- JR Hafer

- The Kingston Trio

- WNEW Radio

- Popcorn Sutton

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- GOP Requiem

- The Camp Grounds

- Oh My Galt

- M Adam Roberts

- A Woman

- Running Man

- Resolution Integrity

- Ricardo Teixeira

- There is a Light

- The Unicorn

- The Future