Personality

David Simmonds

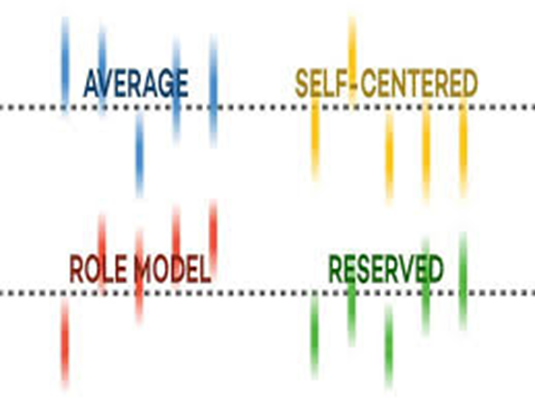

Which one of the four basic personality types are you: average, reserved, self-centred or role model? I’d like to say I’m role model, if only because the other labels sound either bland or downright negative. Having learned what it takes to be a role model, I doubt that I have the chops for it.

People fall between the extremes.

The conclusion, that there are four and only four general personality types, emerges from a large-data study recently conducted by Northwestern University in Chicago. The study examined the extent that people display five character traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Although it emphasized people can and do score somewhere between the extremes, in every category, it nevertheless found clusters of traits or “higher densities than you would expect by chance,” says one of the authors.

For example, most people are average, which I suppose you can say is a tautology. An average person is relatively agreeable and conscientious, quite extraverted and neurotic, but not terribly open. A reserved person is fairly stable in most areas, but low on openness and neuroticism. A self-centred person ranks high on extraversion, but below average on openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness. Lastly, a role model has a high quotient of extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness, combined with a low level of neuroticism.

In a finding that will come as a blinding insight to anyone that has a teenaged child, the study also notes personality types can evolve over a lifetime: younger people rank high in self-centredness, whereas more role models emerge in the elderly. Oh, yes, women are more likely to be role models than are men, which again should come as no surprise to anyone who has known a woman.

My first reaction is to press the panic button and say I must learn how to become more open, agreeable and conscientious. On reflection, it would be a dreary existence if all of us were above average and everyone was a role model. Fallibility is more interesting than perfection. Our role models must have some their own role models, too.

Whether a typical person should ever match up with a self-centred person or whether putting two role models together is a recipe for disaster is presumably the meat for large-data follow up study. Dating sites are no doubt waiting with baited breath for the results.

Accurately locate personality traits.

These findings assume you can accurately discern personality traits. I would rank myself high on agreeableness, for instance, but no doubt just about everyone else on the planet would say the same about themselves. Objective methods are required, but how do you measure someone for conscientiousness, for example; is that a degree of pre-crastination.

Answer: cue the marshmallow test. Walter Mischel devised the marshmallow test a generation ago. This test ranks among the top, that is, most meaningful, test in Social Psychology. Mischel sits aside Stanley Milgram, he studied how willing subjects were to inflict pain on another, and B F Skinner who placed his infant daughter in a box.

Mischel studied gratification, instant and delayed, which crudely approximates conscientiousness. Offered a marshmallow, some children would gobble it down, right away. Others, offered incentives to delay consumption, could wait more than half an hour.

The beauty of the marshmallow test lies in its simplicity. Give a young child a marshmallow and set it in front of her. Tell her she can eat the marshmallow if she wants, but if she refrains from doing so until the tester returns to the room, she can have two marshmallows.

The assumption is that two marshmallows are better than one. The internet is replete with videos of cute four-year-olds, toying with their marshmallows, as they struggle to resist temptation. I like to think of the test as a means of dividing the Homer Simpsons, with little self-restraint, from the world from the Lisa Simpsons, with much restraint, although in the case of the Simpsons, I would use donuts as the bait. I would use Bert and Ernie as alternative examples, but will not because of the recent shadow cast over their gender preferences: this column does not trade in controversy.

Supporters of the marshmallow test say it is a useful prognosticator of success. The extent to which a child can delay gratification, they argue, is an indicator of how well developed is her executive functioning. This, in turn, is a marker for future success in life. The finding has been challenged on the basis its sampling wasn’t broad enough, and others have found that economic status plays a more decisive role in predicting future success than does self-restraint.

Self-restraint and donuts.

Whether success always goes to those who exercise self-restraint is a legitimate question. Sometimes, Mr. Simpson makes a wise decision in reaching for that early donut. I wonder what personality type fits him.

Some readers seem intent on nullifying the authority of David Simmonds. The critics are so intense; Simmonds is cast as more scoundrel than scamp. He is, in fact, a Canadian writer of much wit and wisdom. Simmonds writes strong prose, not infrequently laced with savage humour. He dissects, in a cheeky way, what some think sacrosanct. His wit refuses to allow the absurdities of life to move along, nicely, without comment. What Simmonds writes frightens some readers. He doesn't court the ineffectual. Those he scares off are the same ones that will not understand his writing. Satire is not for sissies. The wit of David Simmonds skewers societal vanities, the self-important and their follies as well as the madness of tyrants. He never targets the outcasts or the marginalised; when he goes for a jugular, its blood is blue. David Simmonds, by nurture, is a lawyer. By nature, he is a perceptive writer, with a gimlet eye, a superb folk singer, lyricist and composer. He believes quirkiness is universal; this is his focus and the base of his creativity. "If my humour hurts," says Simmonds,"it's after the stiletto comes out." He's an urban satirist on par with Pete Hamill and Mike Barnacle; the late Jimmy Breslin and Mike Rokyo and, increasingly, Dorothy Parker. He writes from and often about the village of Wellington, Ontario. Simmonds also writes for the Wellington "Times," in Wellington, Ontario.

- Big Super Bowl Heist

- 2020 So Far

- County Vitals

- Counting Steamboats

- Bernie Finkelstein

- The Desperation Fund

- Hole Foods Study

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- The No-fly Zone

- Valentine's Day Gift

- Calling Bob and Ray

- Sjef Frenken

- The Diefenbunker

- Jack the Misanthrope

- Sex (gotcha!)

- Jennifer Flaten

- All You Can Eat

- As a Possessed Monkey

- About a Bag

- M Alan Roberts

- Lessons of the Bucket

- Wild Horses

- Navidad Negra

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Father and Son

- Reading

- Smile

- Bob Stark

- NHL Playoffs '13-3

- Hear! Hear!

- Grey Cup 2013

- Streeter Click

- The Real Don Steele

- Best of the Best

- Look Now, Pay Later

Recommended

- Jane Doe

- Ex Machina

- Argo

- Recovery Redux

- M Adam Roberts

- Watch Your Mouth

- The Builder

- I Owe You

- Ricardo Teixeira

- The Unicorn

- There is a Light

- The Future