Tiffany in the Balance

David Simmonds

The coronavirus crisis has attached its tentacles to corporate takeovers. The French luxury goods maker LVMH, owner of elite brands in the world of alcohol, such as Hennessy, Dom Perignon, Moet and Chandon; fashion goods, such as Louis Vitton, Christian Dior and Givenchy, as well as jewelry, such as Tag Heuer, Bulgari and Hublot, has backed out of a deal to acquire the iconic American luxury goods company Tiffany & Co. It’s a big mess, with lawsuits flying hither and yon.

The chaos seems precipitated by the coronavirus.

Tiffany and Company was founded, by Charles Lewis Tiffany, in 1837, as a family business. He passed the company to his son Louis Comfort Tiffany under whose tutelage the company reached the apex of its reputation. In 1978, it was sold to Avon Products Inc, which held the investment uneasily until 1984, when control was sold to a private investment group. It became a public company in 1987.

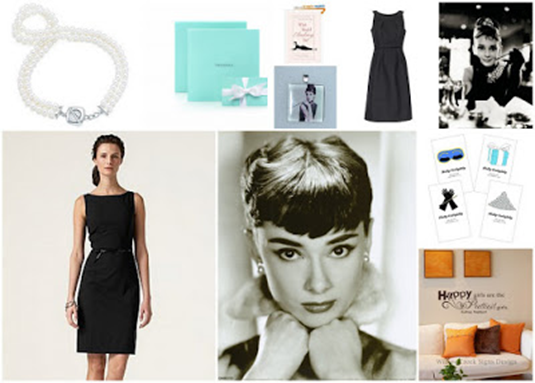

The Tiffany reputation remains stellar. When you think of American luxury brands, the first name that probably comes to mind is Tiffany. Audrey Hepburn had Breakfast at Tiffany’s and was one of two people ever to wear the legendary Tiffany Yellow Diamond, which the company bought in 1879, a year after its discovery.

In November 2019, that year of innocence, the two companies, LVMH and Tiffany, agreed to merge and to complete the merger by June, but that changed to November 2020. In the meantime, the pandemic hit. Tiffany sales fell by a third.

It seems people were not focused on buying the latest piece of bling when they needed to huddle indoors, with only mirrors to show off the gems. At least LVMH had its alcohol division as a fall back. Mind you, there have been fewer occasions in recent months to celebrate with champagne; cognac must have been the meal ticket.

Ultimately, LVMH got cold feet. It expressed doubts on the quality of the Tiffany management. LVMH produced a letter from the French government requesting a delay in the closing of the deal into 2021, ostensibly because of US trade actions against France.

Tiffany sued LVMH, saying it was trying to renegotiate the deal by running out the clock and asked the court to force through the merger on the original terms. LVMH countersued, accusing Tiffany of mismanagement. The costs of on-going litigation mount for both companies.

I have sympathy for Tiffany and LVMH.

Tiffany and LVMH work in a difficult world. Protecting the cachet of core products must be a much bigger game than protecting the integrity of the physical product.

A highbrow reputation must be earned over the long haul and can be lost overnight; supporting a reputation is a ruthless business, I suspect. Everyone likes to see the high and mighty take a hit. No one is likely to spend money on LVMH or Tiffany goods just to show solidarity with them.

With luxury goods, you must constantly watch your inventory. If too much is in circulation, your product will lose its snob appeal and its premium price advantage. On the other hand, if you restrict it too tightly, you may miss the profit opportunity in selling a popular product. Nowadays, luxury goods makers are watched like hawks by environmental and consumer groups as to how they dispose of their excess products.

Then there is the difficulty of whether to pitch yourself only to the upmarket or to make a simultaneous pitch to the middle-range market. Going mid-market appeals to more people, but the risk is that you will turn off your up-market core customer base. Tiffany moved firmly into the latter camp in 1990 by advertising an $850 affordable engagement ring.

Today, you can have a frisson of brand experience by buying a $55 bottle of Tiffany Eau de Parfum shower gel or go the full monte and buy a $275,000 handmade indoor table greenhouse. Tiffany has continued its dual marketing approach by partnering, in recent years, with Lady Gaga and Kendall Jenner, but, somehow, they lack the classy but broad appeal of an Audrey Hepburn.

What will become of Tiffany’s? Will the courts force the parties to marry, despite the objections of LVMH, or will Tiffany go it alone? Can Tiffany go it alone without a partner or will a white knight, such as Avon Products, come to the rescue?

A cynic might say that Tiffany would make the most profit by closing down its 326 stores, worldwide, laying off all its staff, and selling the right to use the brand name to a retailer that is looking to present an upscale image. Imagine if Tiffany branded cutlery were available at your local Canadian Tire store. Your spirits would be reinvigorated, your household beautified. Tiffany could then invest its profits in quantum computing and live happily ever after.

Tiffany run-flats.

It will never happen, will it? Surely even the coronavirus couldn’t push us that far. Perhaps it will happen so your car can ride smoothly on Tiffany run-flats.

Some readers seem intent on nullifying the authority of David Simmonds. The critics are so intense; Simmonds is cast as more scoundrel than scamp. He is, in fact, a Canadian writer of much wit and wisdom. Simmonds writes strong prose, not infrequently laced with savage humour. He dissects, in a cheeky way, what some think sacrosanct. His wit refuses to allow the absurdities of life to move along, nicely, without comment. What Simmonds writes frightens some readers. He doesn't court the ineffectual. Those he scares off are the same ones that will not understand his writing. Satire is not for sissies. The wit of David Simmonds skewers societal vanities, the self-important and their follies as well as the madness of tyrants. He never targets the outcasts or the marginalised; when he goes for a jugular, its blood is blue. David Simmonds, by nurture, is a lawyer. By nature, he is a perceptive writer, with a gimlet eye, a superb folk singer, lyricist and composer. He believes quirkiness is universal; this is his focus and the base of his creativity. "If my humour hurts," says Simmonds,"it's after the stiletto comes out." He's an urban satirist on par with Pete Hamill and Mike Barnacle; the late Jimmy Breslin and Mike Rokyo and, increasingly, Dorothy Parker. He writes from and often about the village of Wellington, Ontario. Simmonds also writes for the Wellington "Times," in Wellington, Ontario.

- Best Political Team

- From Boil to Simmer

- Typewriter or Lathe

- Potatoes & Beans

- Far Away Places

- 24-to-1

- Doing 50, Turning 70

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- The Next Grandiose Idea

- Golf Inspires New System

- Political Slogans

- Sjef Frenken

- Dog Heaven

- The Game

- A Petard Among Friends

- Jennifer Flaten

- Christmas so Soon?

- Mustaine: a review

- Kindle Me

- M Alan Roberts

- Fired Up

- What the USA Needs

- Paint My Face Red

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- Sleepovers

- Fall into Winter

- Summer Time Fun

- Bob Stark

- Ozymandias

- A Team Canada

- Boomerang

- Streeter Click

- Social Effects of COVID

- Content Submission

- Funny Business

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- Beyond the Law?

- Trump GOP and Bribery

- Her Tribute

- Jane Doe

- Recovery

- Guitar Woods

- Watchman

- M Adam Roberts

- Working for the Man

- In the Subconscious

- Lessons in the Park

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Harmony

- There is a Light

- The Unicorn