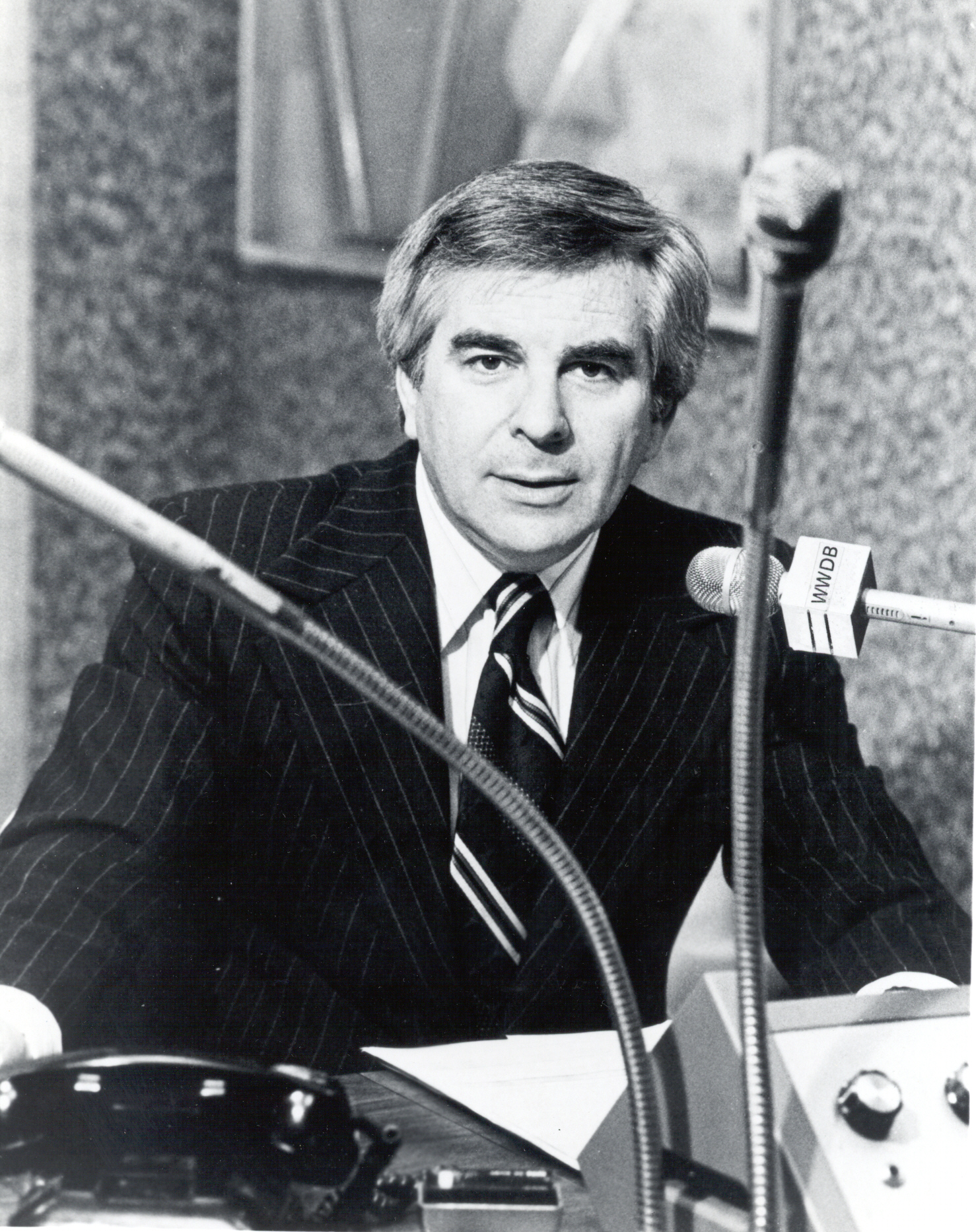

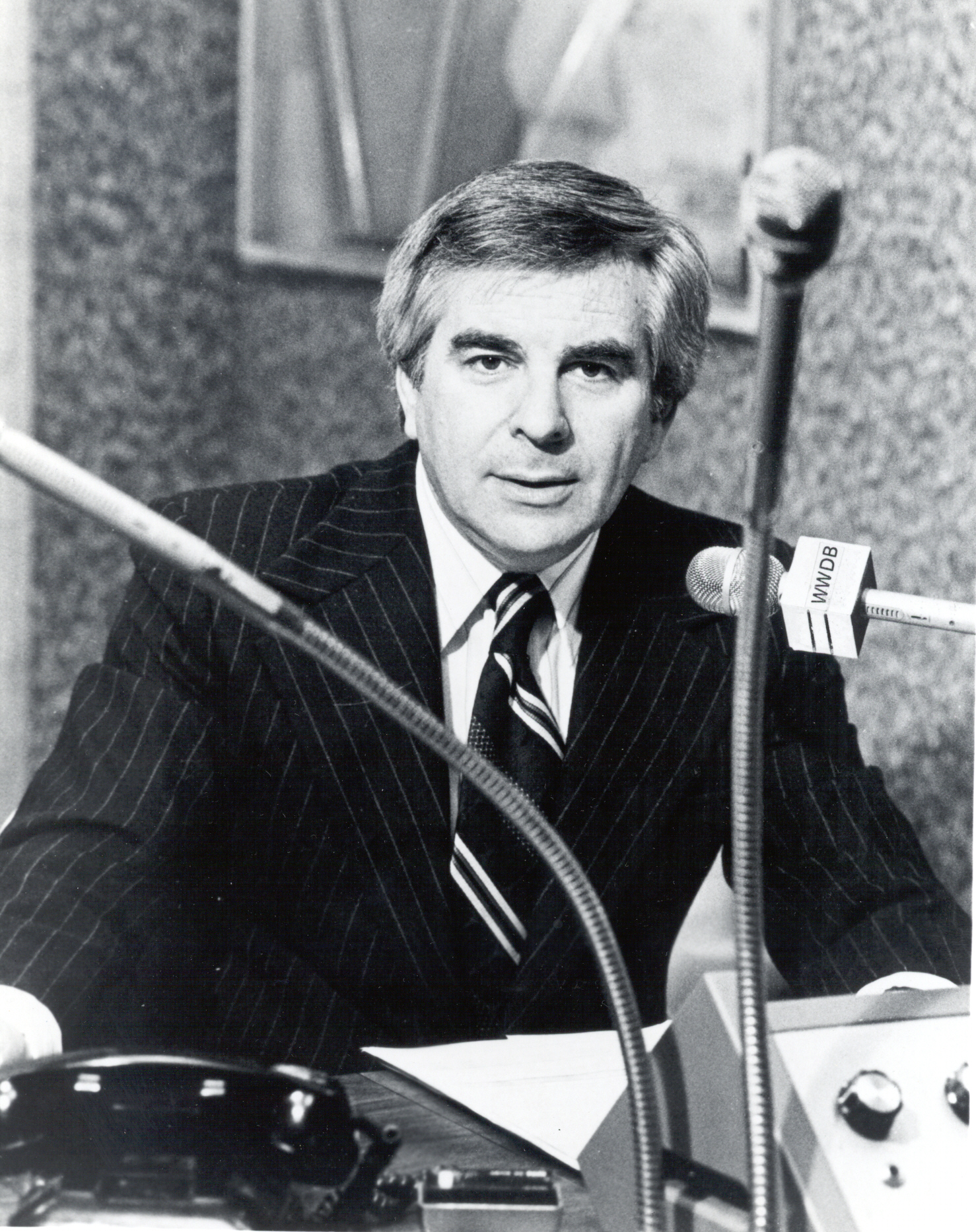

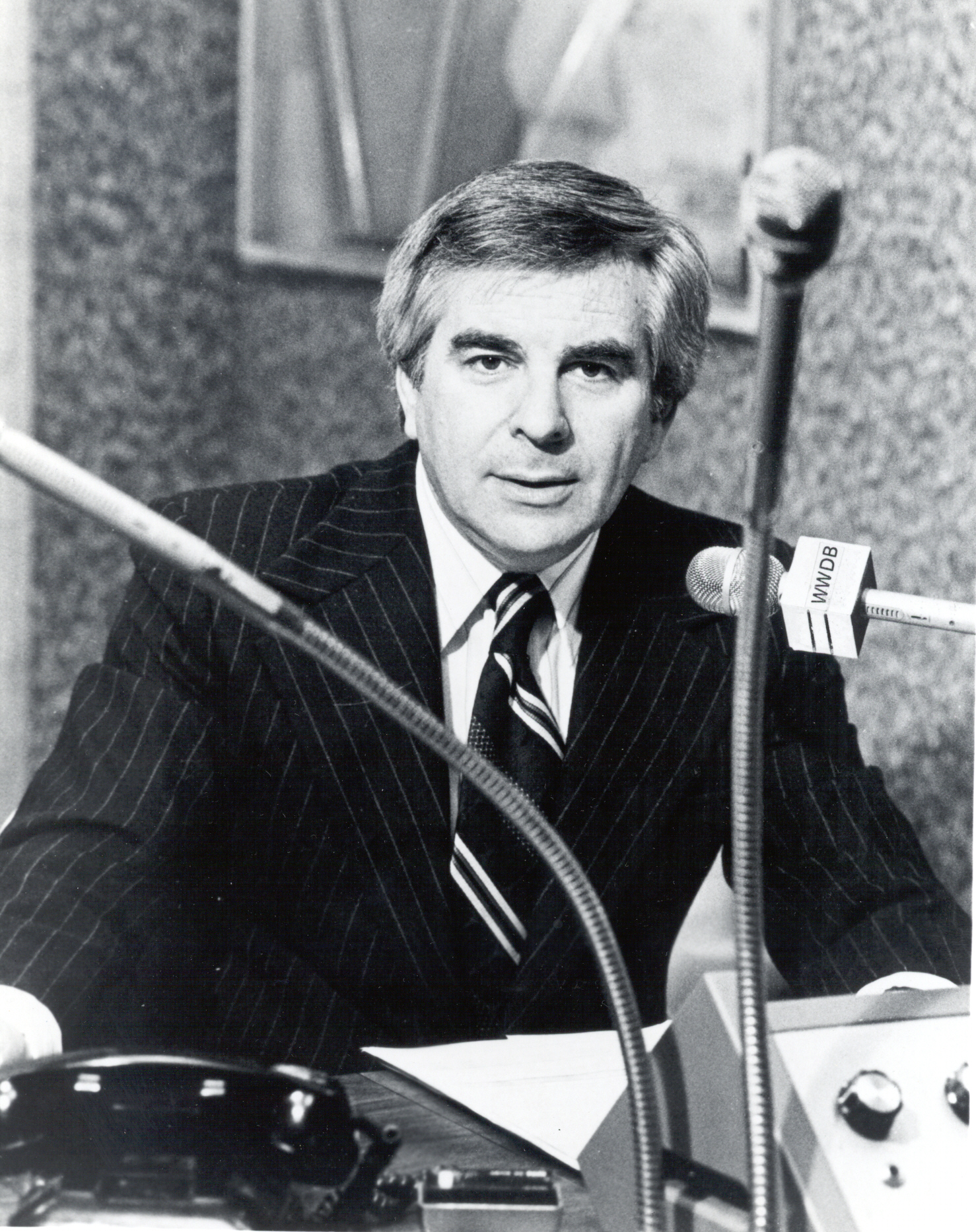

Jerry Williams

dr george pollard

Mouth to Mouth Battle Resuscitated," screamed the 3-deck headline of the "On TV" column, by Jim O'Brien, in the Philadelphia "Daily News" for Tuesday, 27 March 1979.

O'Brien's lead-item that day dealt with the problems Philadelphia talker WWDB-FM was having with KYW-TV, the Group W owned sister station of top-rated all news KYW. It seems TV made a last-minute policy reversal and refused to run WWDB-FM, spots, newly produced and previously approved. The change of policy came about after KYW decided WWDB-FM was serious competition. That occurred just after Jerry Williams (Gerald Jacoby, 1923-2003) arrived and was furthered by Williams complaining he "was not permitted" to reply to a KYW-TV editorial.

The battle was on. Jerry Williams was back in town! Everyone knew it!

Talk radio is a product of the post-war '40s. Williams is its most notable progenitor. He started in radio in 1946 at WYCB, Bristol, Virginia, moved to WETO and then to WKAP, Allentown, Pennsylvania.

It was at WKDM, Camden, that he began talking. That was 1950: “The show ran at noontime,” he says. “It was called ‘What's On Your Mind.’ We didn't have two-way capability then, so I had to repeat what the caller said. Beeper phones were a ways off!"

In 1951, Williams moved across the river to WIP in Philadelphia. He teamed with Harry Smith, and they did a two-man comedy DJ show. "It was afternoons. There was no such thing as am or pm Drive then. There was talk in the market, at the time, but I wasn't doing it. Philadelphia was one of the first major talk markets in the country. They were doing a lot of it from restaurants."

Smith and Williams broke up in 1955. "It was then that I got into talk, seriously," he says. "I did shows from various restaurants in town, interviewing celebrities and stars, politicians and so forth. That was from 1955 to 1957."

In 1957, beckoned by Mac Richmond, Williams moved to WMEX, in Boston (now WITS-AM).

"That is where it really began to come together," recalls Williams. "Up to that point, I was sort of feeling my way about; finding what I wanted to do; what was best; what makes the most money; what the future was all about. In terms of ratings, WMEX was the biggest show I have done. I had shares in the 40 to 50 range."

Being book ended in the 10 pm to l am slot by ARNIE 'Woo Woo' Ginsberg and Larry Glick didn’t hurt his numbers.

"The show was extremely successful in its own right, too. It was the first. It was different. It was two-way, but, most importantly, it was different. That is what made the difference, both in the ratings and in my talk-philosophy."

Pinning down the Jerry Williams talk philosophy isn’t easy. It is most definitely bold: Of course, it is agitating: More to the point, it is intellectually assertive, searching, testing the waters of alternative-solutions pool.

Caring is the critical dimension of what Williams believes talk on radio must, can and should be. Not simply sounding as if he cares, but actually caring. Talk on radio should show caring about the city, the people, the country, the world! This he seems to do instinctively, maybe in spite of himself.

A third dimension is what one might call, "intellectual egalitarianism," the notion all ideas are worth consideration. This connects with his seeming quenchless thirst, his constant testing of the waters. Williams wants to know how far we can go, not where the edge sits.

On this part of his talk philosophy, Williams is expressive. "First, you have to have strong views. Now, that doesn't mean you should be an ideologue. (That is, someone gone wild on one subject and generally one view of it, one perspective.) No, you don't have lock onto an ideologue; just having strong views. I like to call myself a pragmatic democrat. When I see a problem, I try to solve it. Someway! Anyway! I go into it without any fixed ideas on how to solve it. My goal’s to solve it, effectively, efficiently and, hopefully, permanently. It doesn't matter what the problem is; government, the economy – whatever. The approach should be the same.

“Whereas I like to think I have no fixed ideological cure-all, the Barry Farber (WMCA-AM, New York) of the world have the solution before the problem [arises]. Ideologues! First, they say, government can't solve it. No way! Only the private sector can [solve any problem]. Then they apply this predisposition to everything they confront. There is little variation in their thinking."

A fourth dimension of his talk radio philosophy is fulfilment of audience needs as well as expressed wants. People will freely express what they want to hear, and know about; fires, murders, taxes. Generally, expressed wants link to a desire for immediate rewards. Listeners can revel in a vicarious experience supplied by crime and corruption issues, without fear of danger or stress.

Needs offer delayed rewards. People must be told why the cost of living skyrockets, and taxes, too, and they may be affected. Servicing needs conditions people, and helps them cope with a piece of reality that impinges directly upon them. Informed and prepared, they are better able to deal with these things. Servicing needs, then, is critical. It may be what the FCC intends when it says broadcasting must be, among other things, in the public interest. From a social psychological perspective, wants servicing are a form of entertainment; needs servicing as an essential social service.

Jerry Williams left WMEX in 1965. Though not specific as to why he left, it was probably that after eight years Mac Richmond had simply gotten to him. Richmond got to a lot of people! From WMEX, Williams went to WBBM, in Chicago. "That, too, was a very successful show, he says.

"Then I did am Drive for 8 or 9 months … the show was successful, too, [but] I found I couldn't bear getting up in the morning. My body rhythms didn't [work] in the morning – at least for the kind of show I had to do."

After three years in Chicago, it was back to Boston and WBZ, the 50,000-watt clear-channel. Jim Lightfoot had just taken over as manager, and was developing innovative programming. Lightfoot blocked twelve hours of music (6 am to 6 pm), with Carl de Suze, Ron Landry and Dave Maynard; 12 hours of talk (6 pm to 6 am), with Guy Manilla (sports), Williams and Larry Glick.

WBZ was yet another success for Williams. Quarter-hours peaked near 100,000 for his 8 pm to Midnight slot. His share ranged from 15 to 18, and this was in a 31 station market, evenly split between am and FM.

"FM was just about to take-off," says Williams. "FM was just coming alive. There were some good music and underground stations at the time. They just hadn't cut into the market yet. WBZ dominated Boston! We were occasionally getting a 20 share. Those were in the Vietnam and Watergate days; in terms of absolute audience size, it was the biggest talk show, not just in Boston, but across the country, considering the time slot."

The influence of Jerry Williams was awesome, even reaching into the McGovern 1972 Presidential campaign. Williams had received a particularly sensitive and penetrating call from an injured Vietnam veteran just back. The caller, his life dramatically altered by both the injury and war experience, was articulately anti-war. He was rational, perceptive, insightful. Above all, his argument was convincing, powerful, undeniable. "WBZ almost fired me for that," says Williams. "They were vocally unhappy that I gave him (McGovern) the tape. It had been played on the air at least [a dozen] times before he got it. It was really no secret. He could have taped it off the air.

The significance of the tape was secured when each of the three US major television networks featured, on their evening news programs, an extended film clip of McGovern and his advisors listening to it. Their guise was serious. They had found salient support for their position from some- one who had experienced Vietnam. This was damaging! Kissinger's "peace is at hand" statement was yet to come.

Four years later, Williams left WBZ. The circumstances surrounding his departure are a mystery, even to him.

Was it the years he spent discussing the pragmatic and moral issues of Vietnam? Maybe it was the 3 1/2 years he spent discussing Watergate. Westinghouse, the Group W parent company, had deep interests in the Vietnam police action, Nixon and Watergate. Did they feel he threatened their other interests?

"It's possible," says Williams, "but I can It really be sure. Sometimes you can become a persona non grata. You never know why. In my case, they didn’t fire me. We got together, and agreed to disagree. My contract was up. They wanted monthly renewals. I thought that was ridiculous. I left. That was 1976. I had been at WBZ just over 8 years. Ratings were still very high, but once you become a non-person, there is no redemption, no way of dealing with it, and you never find out why. To this day I don't know why."

As fate would have it, the general manager who conducted contract negotiations with Williams, became a persona non grata, himself.

"When he dealt me in," Williams says, "was [when] WBZ went into decline. About the same time, Ira Apple came in to program the station. He didn't know what he was doing and things started to deteriorate, particularly the 6 pm to 6 am audience. Guy Manilla doing sports, me doing 8 to midnight and Larry Glick after midnight. We were contemporary figures. We weren't lost in the dust, playing old Arthur Godfrey records. I think the [major problem] was that Guy Manilla wanted to do something much bigger, which he shouldn't have done.

“In his 6 pm to 8 pm slot he rolled over from sports to issues. People were used to sports, 6 to 8, and issues 8 to midnight. When they tuned in at 6 pm and heard him talking issues it was double confusing. If they had moved [Manilla] into my old time slot doing issues and somebody else into the sports slot it might have worked. Instead they just confused everyone."

Ratings support Williams. Quarter-hours fell from 100,000, in 1976, to 40,000 when Manilla left, in 1978. That’s a 60% drop in less than 2 years.

The next stop for Jerry Williams was WTIC, in Hartford, CN. "I went with all good intentions," he says. "I was going to stay; help them revamp their equipment, their approach to talk and generally participate in building the station to even greater heights."

How did the Hartford audience differ from that of Boston? "Hartford is a small town. It's an interesting place to be all your life …; it’s a small town run by an oligarchy. That's why people like life there. It's nice there. It's pretty, but it's not Boston. It doesn't have the same beat."

Circumstances dashed high hopes. In a couple of months happenstance and the rigor of commuting from his home near Boston became too much. Williams headed home.

Again, he found himself at WMEX, in Boston. Mac Richmond had passed away. The family was selling the station. "I wasn't aware of it," he says. "They were offering me all sorts of money to stay; bonuses, the whole thing. They never told me they were selling and part of their deal was that I stayed on."

Meanwhile, WMCA, in New York, beckoned. “It was my first chance to take a crack at my hometown,” says Williams. Obviously, it was a dream to be able to do that, and to replace Barry Gray. So I decided that no matter what they offered I would go to New York, and I did.

“Barry Farber wasn't there at the time. Bob Grant was still there. It was kind of a big thrill for me to be there, in that time slot, but the station still had its problems."

Circumstances, again, intervened. “My mother was ill,” says Williams. ““My family was still in Boston. I'd been on the road for about a year, and it was getting to me. I was diverted by a lot of things. After a year or so at WMCA, I decided to come back to Boston.

“WMEX – by that time the call letters had been changed to WITS by the new owners – beckoned [, again], and I decided to give up New York for my family which was more important to me."

New owner Joe Scalon had taken over WMEX on 1 April 1978. The place simultaneously collapsed. The day and date of the take over was fitting.

"It was very disappointing for everyone," says Williams. "I decided to stay only until September. I tried to get along with [Scalon], but he was very strange. He doesn't know anything about radio – at least he didn't then. He kept moving people around, lying and breaking promises."

“When [WMEX] asked me to come back, they said they needed me desperately. Yet, when Scalon comes in, he says he [feels] no obligation to me, whatsoever. I knew I wasn't in the right place. The hostility [that] pervades a lot of radio stations isn't the kind of atmosphere I want to work in – I can't [work] that way."

Was there any other place for him in Boston?

"No! When you stay in a city – I'd been there for 21 years at the two stations with talk – you can become second string if you move from station to station too much. I have a friend, Bill Marlowe, who’s one of the great jazz jocks in the country. He worked a number of Boston stations, and New York as well, but now he is at a small, second-rate station in the suburbs. He has to buy his own time in order to get on the air.

“This is why I think that if you stay in a city and you see the city as the most important thing, you can become second string very shortly. It isn’t necessarily inevitable. It just happens often! The secret, I guess, is to find a large market where you are going to do well and be free to be able to make whatever changes are necessary until you find it."

Autonomy is all, and it was this sense that led Williams to leave Boston for Washington DC.

“I just knew I had to get out of Boston,” says Williams. “I had to leave,” he says, with obvious remorse. I knew there were no opportunities for me. None at all!

Click here for a list of all Grub Street Interviews

Interview edited and condensed for publication.

dr george pollard is a Sociometrician and Social Psychologist at Carleton University, in Ottawa, where he currently conducts research and seminars on "Media and Truth," Social Psychology of Pop Culture and Entertainment as well as umbrella repair.

- David Rich

- What Was, Isn't Now and Might Be

- Larry Glick, was 86

- Tom Konard

- Carl de Suze

- Allen Klein Jollyologist

- Neal Gumpel

Click above to tell a friend about this article.

Recommended

- David Simmonds

- Question Resolved

- Taking a Flyer

- Doing 50, Turning 70

- Sjef Frenken

- Rooting for the Underdog

- New Words Defined

- The Bettor Way

- Jennifer Flaten

- Peeping

- March Tan

- In the Gutter

- M Alan Roberts

- Doing Time for No Good

- Ode to Officer Cole

- Brain Abusers

Recommended

- Matt Seinberg

- 2014 TV Season

- Road Tests

- Police & the Public

- Streeter Click

- Junos Boring, Always

- Reviews of All Sort

- Boston Blackie

Recommended

- AJ Robinson

- No Aim

- One More Ride

- Love Among the Ruins

- Jane Doe

- US Election 2016

- Guitar Woods

- Mrs Doubtfire

- M Adam Roberts

- Essence of a New Day

- The Great Lie

- I Owe You

- Ricardo Teixeira

- Monkey Business

- The Unicorn

- There is a Light